Deaccession Misperceptions: Check the Facts before Critiquing the Professionals

Ruth Osborne

It seems there needs to be a re-education on the dangers of rush and/or mass deaccessions at museums and the ways they strongly point to collection mismanagement. A recent article on artsy.net, a site established not 10 years ago mainly for private art galleries, fairs, and sales, and with an emphasis on contemporary art, has seen fit to criticize museum professionals’ concern over the current deaccession and collection stewardship crisis.

Former college art gallery director Michael DeMarsche and retired economist Bob Ekelund insist that institutional guidelines governing the ethics of deaccession procedures are the “outdated rules [that] are killing museums.”

Among the many inaccuracies this article contains are that museums are running into financial issues due to factors that are “out of museum management’s control”: “declining donations…adverse local situations…and increasing storage costs for housing ever-increasing acquisitions.” But if a museum is in dire financial straits for object care due to acquisitions and storage space needed for those new items in the collection, wouldn’t that be truly due to misguided purchasing when there is not the budget for it? If a museum’s budget is in danger because it’s dependent on expected donations, is there not any board responsibility for setting such budgetary expectations and not understanding the donor climate?

The authors of this article propose deaccessions and sales as a way to save money in order that they might “mount more shows, and reduce admission costs”. But admissions don’t actually pay for a substantial portion of any museum’s budget. And yet, they insist that the raised admissions at the Met for out-of-towners has made “one of the greatest art collections less accessible than ever.” Granted, this is only for those outside the tri-state area. And those visitors coming from further away do happily pay more than the now-required $25 Met admission fee in order to see a Broadway show, to dine out, and experience other cultural diversions. Not to mention that the full-price admission ticket also enables them to return for visits for a 2nd and 3rd consecutive day.

The above statement implies that spending more on “shows” (why not “exhibitions”?) is the main way museums are being impeded in their growth. If spending more on “shows” is behind a museum’s tearing apart its collection, should not that institution question whether these initiatives are at the core of its own mission? Why is maintaining care of its collection hampering its ability to display works? What about the costs of lending exhibitions – loan fees, transportation costs that inevitably pose great risk to works, etc. – that might be hampering a museum’s ability to care properly for works in the permanent collection? Or are the authors saying that the ultimate purpose a museum should serve is as blank walls for a rotation of outside works instead of develop its own collection identity and serve as a dependable resource for the surrounding community that makes repeated visits?

In response to the article, Cristin Waterbury, Director of Curatorial Services at the National Mississippi River Museum in Iowa, conveyed that she was:

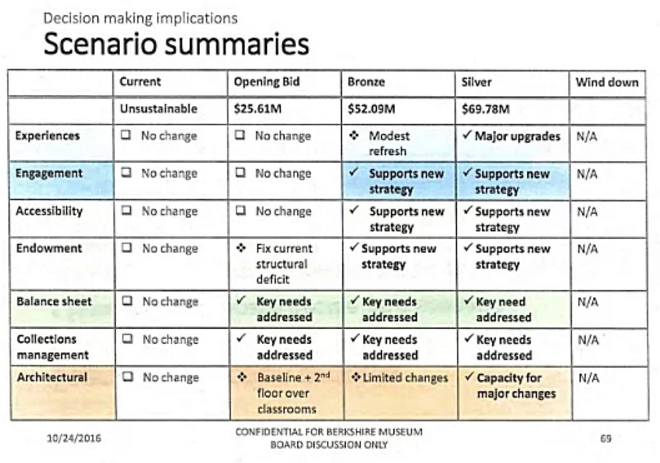

[…] disturbed by the incredible number of inaccuracies [this article] contains. We all know what a hot button topic deaccessioning has become even among the general public recently, particularly following the Berkshire situation, but I for one am concerned about this portrayal of the field.

Meanwhile, Janice Klein, Executive Director of the Museum Association of Arizona and Board Member of the Small Museum Administrators Committee of AAM, says “the article is full of inaccuracies” and “there are many misunderstandings (even within the museum community) about deaccessioning”.

Their next area of complaint is the storage of art collections that are not on display or traveling on loan. It should be pointed out that one of the authors, Mr. DeMarsche, prides himself on having overseen the construction of several new award-winning museum buildings and raising the tens of millions of dollars required. Why bother complaining about storage costs when one has been so extensively involved in prioritizing and promoting construction of them? They use for reference a study of the cost of storing America’s art being over $300 million annually. Well, the study actually comes from the graduate program at RAND (which stands for Research And Development) – a nonprofit corporation founded in 1948 as a think tank for the U.S. Armed Forces. Its mission is stated as “a nonpartisan research organization that helps improve policy and decision making through research and analysis”. You can find the study by Ann Stone, titled “Treasures in the Basement? An Analysis of Collection Utilization in Art Museums” published online here. An interesting choice of supportive research to use for such a harsh argument against the cost of caring for works of art.

We recommend, for your consideration, the proceedings and breakout session findings from a conference held by the American Alliance of Museums last December called “Don’t Raid the Cookie Jar: Creating Early Interventions to Prevent Deaccessioning Crises.” Better to understand the factors of mismanagement that actually lead to a board proposing deaccessions, from the point of view of collections professionals who’ve worked in the nitty gritty, in order to really know the factors posing threats to museums today.