Satellite Museum Dreams and Misgivings in Abu Dhabi

Ruth Osborne

The long-awaited opening of the Louvre Abu Dhabi Museum is actually happening. On November 11th, the site is set to open to fan-fare: “workshops, tours, music, and international performances and a few surprises along the way”.

Courtesy: Christopher Pike / The National

This is all thanks to generous loans from the Musée du Louvre in Paris, a lending relationship we’ve covered previously. But it seems this Abu Dhabi satellite museum may not be joined by its loan-heavy partners – Guggenheim and Zayed National Museum – for another several years. These three museums, along with a Performing Arts Centre and Maritime Museum are all part of the world-class leisure destination and cultural center that developers hope Saadiyat Island will be.

News broke this week that the British Museum has prematurely ended their 2009 agreement to loan objects valuing up to £1bn to the ZNM. But this isn’t the full picture. A communications personnel from BM has told ArtWatch that the contract was actually “to deliver consultancy services” to ZNM in its development phase. Furthermore, “The Museum had never agreed a loan list with ZNM…To clarify the relationship hasn’t been terminated, but the development phase concluded in spring this year. The contract runs until 2019.”

Reports that the contract ended are, according to this representative, misguided, and “the ongoing development of the collection will be undertaken by a dedicated in-house team at TCA” [Abu Dhabi Tourism & Culture Authority]. But the ZNM is still experiencing construction delays. It was scheduled to open its doors in 2013, but now Foster + Partners, the architects responsible for executing the ZNM building, estimate completion in 2020.

And it was earlier this year that Thomas Krens, former Director of the Guggenheim Foundation, betrayed his own misgivings about the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi site (scheduled to open 2012). In an interview in March, Krens emphasized the naïvety to plan construction of so many huge museums all at once in Abu Dhabi: “we don’t need all five of them up and running at the same time”.

Saadiyat Island rendering, with the Louvre (left), ZNM (center), and Guggenheim (right). Courtesy: Saadiyat Cultural District website.

So why is it that these seemingly beneficent plans for public museums in Abu Dhabi are fraught with mishaps and delays? Amidst the media excitement for shining new museum buildings and the optimistic promises of a center where global culture and art to intermingle, one thing that has been left out is the actual physical risk of transporting all these loan objects from London to Abu Dhabi. Art is fragile. It becomes accustomed to a climate and is open to risk of destabilization once it is shocked out of that climate. Once a work is removed from a gallery or from storage, it would be boxed or crated, would make its way to a large truck, be driven over roads and highways and loaded onto a plane, then raised thousands of feet in elevation for over 3,000 miles, touch down in Abu Dhabi, and then be trucked again and finally installed in a completely new climate. Works have been easily torn, broken, and warped in transit by major museums in the past. Increasingly so with the opening of international traveling exhibitions and satellite museums in different countries.

Those objects at risk in the Louvre’s loan agreement include:

Leonardo da Vinci, La Belle Ferronniere (Musee du Louvre)

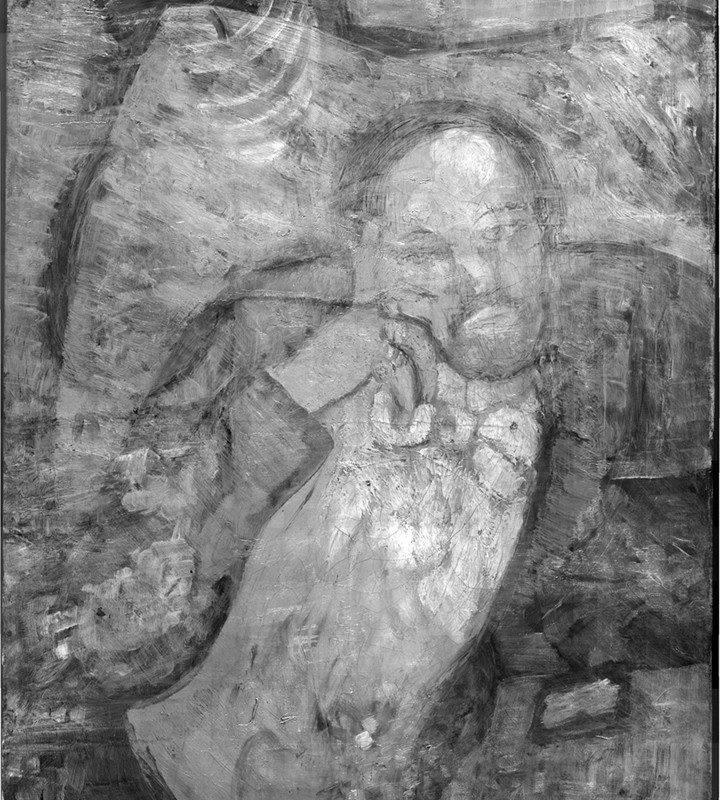

Vincent van Gogh, Self Portrait (Musee d’Orsay)

Balthasar and Gaspard Marsy, Horses of the Sun (Palace of Versailles)

Paul Gauguin, Children Wrestling

Piet Mondrian, Composition with Blue, Red, Yellow and Black

We encourage our readers to remember the implications of transporting these – and future – works of art. And also to ask – who is really benefiting from these initiatives?

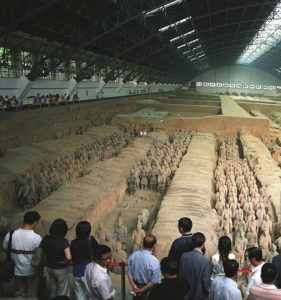

Perhaps an even more impressive deal was made by British Museum to secure the loan from China of twenty terracotta statues of the warriors of the first Chinese emperor, Qin Shihuangdi, dating to the third century BCE. The twenty are just a small fraction of the 1000 figures that were unearthed in 1974 – about 7000 still await excavation – but it is the largest amount of this material to ever leave China. Previous exhibitions in Germany and Austria were composed of copies only, though still drawing impressive crowds. The Chinese government has recently made claims that a current exhibition at the Hamburg Museum of Ethnology is made entirely of copies, and the museum has been forced to offer refunds to the 10,000 visitors who have seen the show since it opened in late November.

Perhaps an even more impressive deal was made by British Museum to secure the loan from China of twenty terracotta statues of the warriors of the first Chinese emperor, Qin Shihuangdi, dating to the third century BCE. The twenty are just a small fraction of the 1000 figures that were unearthed in 1974 – about 7000 still await excavation – but it is the largest amount of this material to ever leave China. Previous exhibitions in Germany and Austria were composed of copies only, though still drawing impressive crowds. The Chinese government has recently made claims that a current exhibition at the Hamburg Museum of Ethnology is made entirely of copies, and the museum has been forced to offer refunds to the 10,000 visitors who have seen the show since it opened in late November.