A Look at Art Conservation in the News.

Ruth Osborne

In order to get a better sense of how conservation is presented to and perceived by the public today, ArtWatch has undertaken an overview of art conservation as it has appeared in the media over the past year.

Thoughts and opinions on the purpose of conservation have developed and changed over the past 150 years as society considers new scientific technologies. Noticing trends in news coverage of conservation interventions, as well as the state of the field as a whole, will allow for an understanding of the role of conservation as it is understood in the 21st century. This post will consider the following:

(1) How are conservators represented in relation to the works they’re treating?

(2) What is given precedence in reports of current conservation treatment, the work itself or benefits for the field at large?

(3) According to news coverage, what is the ultimate goal of modern conservation and what is being put in place to further this goal?

Patricia Favero, conservator at The Phillips Collection, with Picasso’s The Blue Room and showing its under layer. Courtesy: Evan Vucci/AP.

Art conservation as a field was born of the need to care for works of art as they experienced the ravages of time and misuse. Taking this into consideration, would it not come as a surprise that so many news stories covering the work of conservators focus on the promise of discovery instead of preserving the physical nature of the work from further deterioration? Is the act of prodding for findings beneath layers of paint with infrared imagery to discover an underlying image that the original artist painted over considered “conserving” the work from future deterioration? Regardless of how this fits into contemporary or classical theories of conservation, research into Picasso’s The Blue Room was still presented in the media last June as being part of the work’s conservation.

Just this week, The New York TImes reported on a new “discovery” of Jackson Pollock’s technique revealed by conservators treating his 1947 Alchemy at the Guggenheim Venice. His intentional, rather than random, paint-splattering technique has in fact been acknowledged by scholars before. Time magazine’s art critic Robert Hughes wrote in 1982 that: “…Pollock–in his best work–had an almost preternatural control over the total effect of those skeins and receding depths of paint. In them, the light is always right. Nor are they absolutely spontaneous; he would often retouch the drip with a brush.” It is certainly interesting how computer imagery can unpack the layers of this painting. But cannot the eyes of connoisseurs already perceive his technique by examining the painting and its underlying grid in a thorough visual analysis, instead of relying on computer analysis to reveal his method?

But dialogue is being pulled away from connoisseurship and its capabilities and towards a heavy reliance on science to achieve “objective” proof. Is science truly as definitive and free of error as is assumed by the media?

Leonardo da Vinci, La Belle Ferronière, 1490-96. Courtesy: Louvre, Paris

After announcement was made in February 2014 of the Louvre’s plan to restore the extremely vulnerable La Belle Ferronière by Leonardo, and after Michael Daley of ArtWatch UK questioned the safety of this plan, several months later it was revealed that it was to be the first Leonardo to show in the Middle East. Its planned transportation to the Louvre’s new satellite museum in Abu Dhabi was released to the press in October. This risky proposal to transport an extremely important confirmed Leonardo was precisely what necessitated its conservation, no doubt, as Louvre representatives related: “For such an important painting it is very important for us to have time. The first [restoration] committee met last week and now we will restore the painting and take all the time we need [and then] we will be very proud to show the restored painting.” But how does one simply gloss over the danger of transporting an already vulnerable painting overseas for temporary exhibit? Is it to be assumed that restoring it will make it less susceptible to damage? We have already had our share of works severely ruined on transport within the same country – even within the same museum building.

On another Leonardo panel surrounded by much controversy is his Lady with an Ermine, which has been altered by several restorers over the centuries. In 2007, ArtWatch reported on the promise of the picture’s digital reconstruction through a multispectral high-res camera. In these investigations, the role of conservation proposes to help undo the work of past ill-treatments and restore a more authentic version of the original. However, as we wrote:

“It is critical to remember that the conclusions drawn as a result of these diagnostic tests are not necessarily correct. Even the most ‘objective’ scientific evidence requires interpretation, and so many of the public announcements that have been made, touting the newest discoveries of the original intentions of the artist, are not universally agreed upon, nor should they be…the concern lies in the knowledge that historically latest technologies have often been used to promote rather than replace restorations. The fear in this case is that believing to fully understand what lies beneath the surface of an artwork will embolden restorers and justify their aims to go looking, with their preconceived notions, for what they now expect to find.”

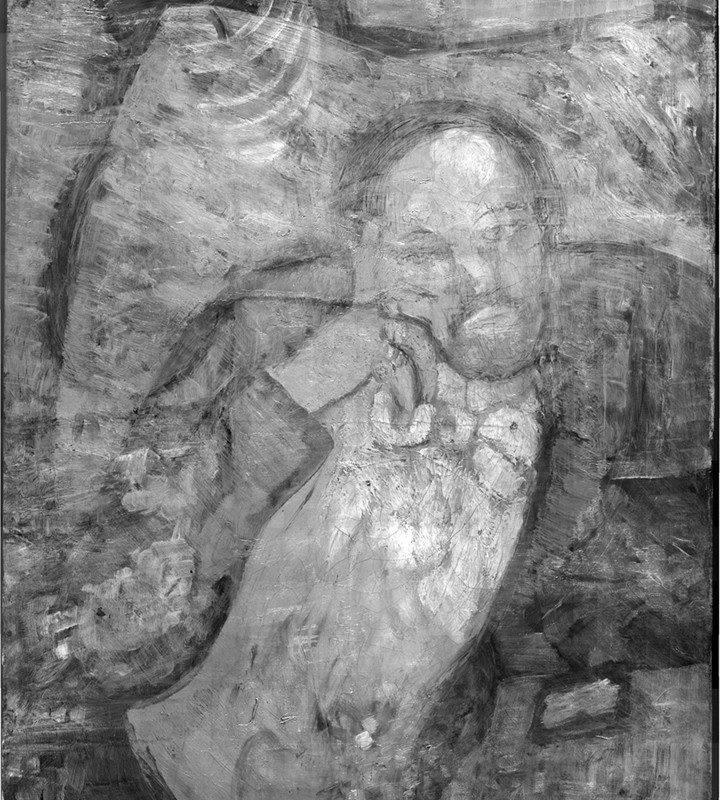

Digital imaging showing three different versions of Leonardo’s Lady with an Ermine. Courtesy: BBC News.

Come 2010, ArtWatch UK argued against its traveling to London on loan for a National Gallery exhibition. To prevent damage in transit, and to ready the painting for blockbuster exhibit, pieces are often sent to the conservator’s studio with the hope of increasing stability in the work. But the more a painting is handled and touched, the more its integrity is altered, no? BBC coverage last fall revealed conservators were still working with the panel to reveal “extraordinary revelations” about Leonardo’s work through this process. The reporter highlights the promise of new discoveries about Leonardo’s method as this digital digging has used “intense light” emitted from a multi-lens camera to make visible three different stages of the canvas. Who knows what this might mean for any future proposed traveling exhibitions on Leonardo’s process for which this work could be put at risk again?

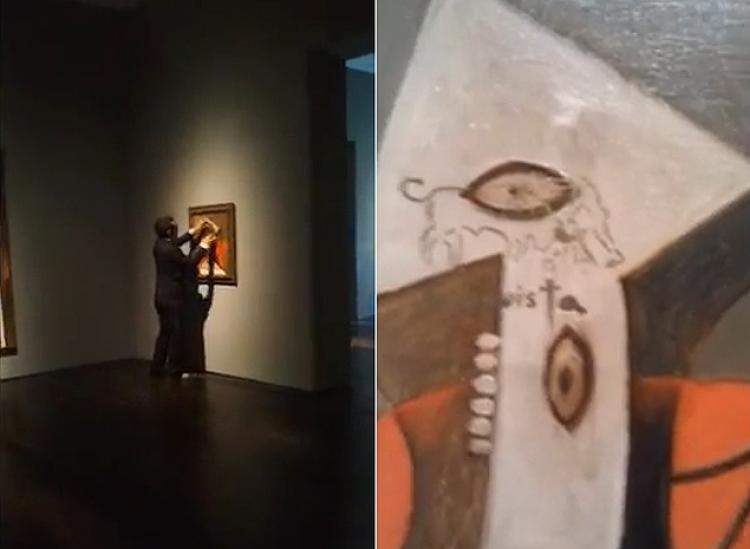

Conservators’ abilities to unravel mysteries about the artist and his subjects with the help of technology was certainly a popular theme in 2014. It was seen in the multiple reports on the “artist’s original intention” that emerged from Gustave Cailleboite’s Paris Street; Rainy Day at the Art Institute of Chicago. Revelations about the artist’s true palette and the canvas’s true dimensions abounded. Here, the conservator serves to uncover a truer version of Cailleboite that had been “hidden” for decades since its last restoration (of an unknown date). Under old varnish, the sky was found to be a more saturated blue and to contain greater light and movement in its surface gradation. Sharper details overall, according to this report, have now altered relationships between the figures and buildings in the composition.

Art Institute of Chicago conservator Kelly Keegan with Gustave Caillebotte’s Paris Street; Rainy Day. Courtesy: Art Institute of Chicago.

One article on the Art Institute’s website even suggests that: “The result is a transformed sense of light and atmosphere that is likely to change the way viewers respond to Caillebotte’s vision of 19th-century Paris and its people.” But does the woman’s hand inserted into the central man’s arm not still indicate their relationship as walking partners? Though the skies have cleared up a bit, wasn’t it presumed this would happen with cleaning of the varnish? Even if the sun may be about to come out, does it really reveal all that much about the artist’s true intentions, as the figures’ umbrellas are still up to protect from rain?

Meanwhile, the The Wall Street Journal reported that this treatment is now the reason to confirm the artist’s designation as an Impressionist: “As a result, curators now believe Caillebotte is likely to be viewed more as a bona fide Impressionist and less a traditional realist.” But wasn’t this already assumed by scholarship? Is this treatment really a breakthrough, as the media might have us believe?

These breakthrough discoveries were only made possible by a series of scientific tools, including infrared imagery, microscopy, and UV light and X-Rays, apart from the actual cleaning via swabs. While it is certainly important to have a solid understanding about a work’s makeup before treatment, will all works now expect to reveal hidden secrets every time they are cleaned? Have the expectations on a work of art increased, and will this help or hurt the integrity of works in the long run? The notion about conservation revealing hidden secrets in a painting continued in coverage of Villanova’s two-year treatment of the Triumph of David in September. In this case, the news report touted the x-ray and infrared tools that allowed conservators to “see into the painting.” According to this coverage, conservation once again aims to return works to, what is presumed to be, a more authentic state.

In a related issue, conservation has also been promoted for its “forensic” capabilities for authenticating authorship of works. Last March it was reported that two canvases by the nineteenth-century American romantic painter Martin Johnson Heade underwent testing at the Atlanta Art Conservation Center to prove their authorship through the existence of the artist’s finger print and brushstrokes, after being denied by Harvard’s Fogg Museum. In this press release, lab testing is referred to as “forensic science” that should take precedence alongside the connoisseur’s trained eye: “…the public needs to realize that connoisseurship has to adapt to a new and demanding educational standard. That standard I believe will become the future of proper art attribution…”

Henry Lie, Director of the Harvard Straus Center for Conservation. Courtesy: Index Magazine.

Hand-in-hand with the claimed abilities of science and technology to do what the human eye is no longer trusted to, came unreserved praise for new high-tech conservation lab techniques. Reports on the newly re-opened Harvard Art Museums emphasized above all the dynamic influence of science in the origins of modern conservation: “it was really the beginning of the field…the first time a science-based approach was taken to looking at these materials.” Meanwhile, the role of new “optical illusions” was the focus of one article on conservation studies at American universities. According to this article, the microscopy, nanotechnology, and x-ray tools conservators use allow them to bring back to life that which was once considered lost. Terms like “forensic tool” are used. But can we truly bring back something from the past? Will all traces of time truly be wiped away? That seems to be what this reporter would have his audience believe is possible.

Finally, the last line from an article entitled “What does a conservator do?” adds rather presumptuously: “Above all they are soothsayers, probing cultural materials to reveal the secrets of how and when they were made, and how they will survive into the future” (emphasis added).