The Words of Conservation: Manet, Pastiche, and Authenticity at the Guggenheim

By Ruth Osborne

Typically, when high-dollar conservation efforts are promoted in the news, it is said that they have effectively enhanced the clarity of the work to the artist’s most authentic original intention. In fact, most of the language promoting months- and years-long treatments of major works in the art historical canon aims to convince the public that the motivation behind these treatments will bring today’s museum-goers a truer vision of an age gone by. This is often coupled with offering the public a truer understanding of the artist’s genius; the artist as “genius” is itself another interesting matter. Nonetheless, the same motivation that brings modern period dramas awards for authentic costume and set design, despite the flimsy acting and plotlines, is the motivation towards authenticity that is recognized and honored by media coverage of conservation projects. But is such treatment on a work of art really bringing to us a truer, more rich understanding of the artist or his/her age past? Or are we searching around a canvas without knowing something more dramatically “authentic” is beneath the surface in the first place? Is this too close to our larger cultural yearning to present the reality of (often unscrupulous or unjust) things as they are which have previously been kept hidden from public knowledge?

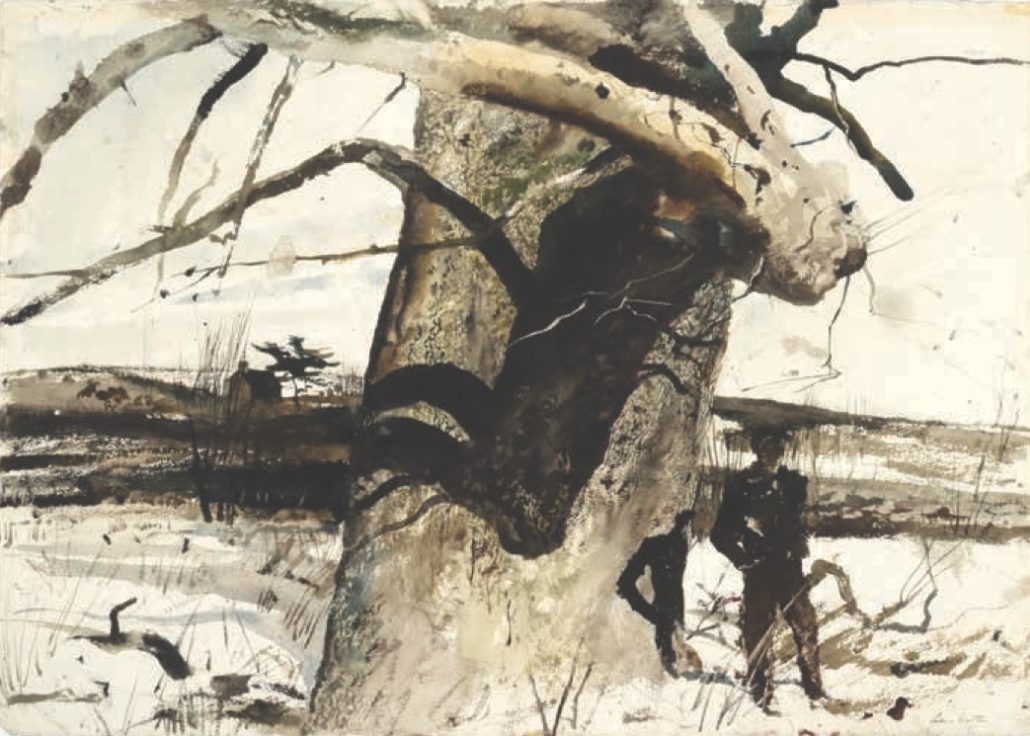

Édouard Manet, Woman in Striped Dress (before and after treatment), 1877–80. Oil on canvas, 174.3 x 83.5 cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Thannhauser Collection, Gift, Justin K. Thannhauser, 1978. Photo: Allison Chipak. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 2018.

Éduoard Manet’s 1877-80 painting Woman in Evening Dress – now, thanks to this treatment, re-titled Woman in Striped Dress – will be exhibited for the first time outside its home at the Guggenheim collection in New York since 1965. This the reason the Guggenheim ever proposed the painting for treatment to the Bank of America Art Conservation in the first place – so that it could go on a world tour with the rest of the Thannhauser Collection of other Impressionist, Post-Impressionist, and early modern works.

From first glance, the painting looks much blander in tone and contrast. Funny that color is typically the opposite of what conservation treatments proclaim to “reveal” about a painting. Indeed, press surrounding this Manet treatment promotes the new tones of grey and violet that appear as fresher and help support the first scholarly description of the painting by Théodore Duret in his 1902 monograph. Duret describes the stripes on the dress as “grises-violettes” (gray and blue-violet). The Guggenheim insists that the cleaning has now permitted a re-naming of the painting from Woman in Evening Dress to Woman in Striped Dress. (For a refresher on color, contrast, and troublesome conservation efforts, see the ArtWatch UK posts on the much-celebrated but also greatly damaging conservation of Michelangelo’s Sistine ceiling here and here.)

But when you watch the video on the Guggenheim website, it seems that the treatment has actually significantly lessened the contrast in the background, as well as the texture in the dress, from the before-conservation photo:

https://www.guggenheim.org/video/unveiling-edouard-manets-woman-in-striped-dress

One wonders about the “several layers of thick, discolored varnish and retouching that had been applied after the artist’s death and before the painting entered the Guggenheim collection”, and what exactly these were made of that enabled them to be safely removed from the work by “a careful cleaning”. One press report describes one the layers as having created “a greenish-brown resinous coating” over the work. After additional inquiry to the Guggenheim as to the application of these excess layers applied after Manet completed the original work, they share their guess that the first was applied between 1883 and 1902, and the second “probably after it passed into Thannhauser’s hands in 1928.” As to the makeup of the reportedly surprisingly “syrupy” varnish:

Scientific analysis determined that the varnish was of a type not commonly used on paintings, but rather one frequently employed for wood furniture or musical instruments, which has a deep, rich tone that discolors as it ages. Such a dark, syrupy, glossy varnish, while appropriate for a wooden substrate, is not suitable for a painting, particularly a modern one.

[…]

Py-GC-MS analysis was performed by Federica Pozzi, Metropolitan Museum of Art. The varnish was composed of a mixture of oil and a diterpenoid natural resin belonging to the Pinaceae family.

Conservators on this project also shared that this large-scale three-year project spanning admit that they were unable to remove “some, but not all, of the posthumous retouching”, even though they also insist these later additions have “a deadening, flat effect”, “transmogrified” the model’s appearance, and represent “an egregious departure from Manet’s design” of the setting.

The consensus was to judiciously remove the deeply discolored varnish and select areas of retouching that covered important details of Manet’s original composition or his exceptional and delicate brushwork. This treatment approach reflects a philosophy that privileges the artist’s hand while keeping in mind the overall aesthetic of the painting.

But they ultimately conclude that the painting as it is post-treatment in 2018 “now better captures the spirit of modernity perhaps not fully appreciated at the time of its painting.” Does this not make the painting still a pastiche? Especially when the praised return to a more “authentic” violet-hued striped dress is dependent on the earliest documented photographs that rely on the alteration of hues by one of two 1880s photographic processes? According to the Guggenheim, these processes

did not precisely reproduce all the colors in the tones of the black-and-white photograph with relative accuracy […] warm colors such as yellow, orange,and red appear very dark, almost black […] while cool colors, including blues and some greens, appear light […]

Not to mention that this first photograph documentation was taken posthumously, during the time of the supposed first over-painting and varnishing.

The promises of modern conservation treatments is that, according to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C, “Yet more discoveries possibly await” (for reference: see our recent post on the lasers used on a Fragonard at the Gallery not for cleaning, but to promote discovery through conservation). This has been the case in the past few decades of conservation promoted as a tool for “discovering” the artist’s previously unknown secret intentions, rather than treating fragile paintings simply to promote physical stability of the canvas for future generations (see our post on Picasso’s The Blue Room at the Philips Collection in D.C.). Sometimes these treatments completely alter the work in question, and yet still vow to adhere to what ArtWatch UK Director Michael Daley has dubbed the modern “cult of simulated historical authenticity” in art (see the article “The New Relativisms and the Death of “Authenticity”):

picture restorers thrive precisely by undoing and redoing each other’s work. Because painting is not an interpretive art form but a concrete one, the artistic consequences of such interventions can be deadly. Painters bequeath not scores to be realised through performances but fixed, artistically-live objects. Such unique creative works can be rendered artistic corpses through a single bungled restoration or be progressively falsified through the “Chinese Whispers” of successive restorers’ interpretations

[…] Unlike genuinely creative people, restorers can never concede technical errors or aesthetic misjudgements for fear of implicating the curators, trustees and sponsors who authorize and fund their actions. Museum politics demand that whatever is done last must be proclaimed right and better than before.

Senior Curator Vivien Greene says of the conservation department’s work on this Manet that “We try to get to the truth of things, literally and conceptually.” But is it possible that major museums and the mainstream media are promoting invasive conservation operations that damage works with the sometimes heroic guise of revisionist history?

Gillian McMillan, Associate Chief Conservator for the Collection, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, at work on the painting. Photo: Kris McKay. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 2018

For more information from the Guggenheim on where you can see this restored Manet in person:

“Van Gogh to Picasso: The Thannhauser Legacy”, including nearly fifty objects from the collection, will be on view from September 21, 2018 through March 24, 2019 at the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao. A second presentation will follow at the Hôtel de Caumont, Aix-en-Provence, France, from May 1 through September 22, 2019.

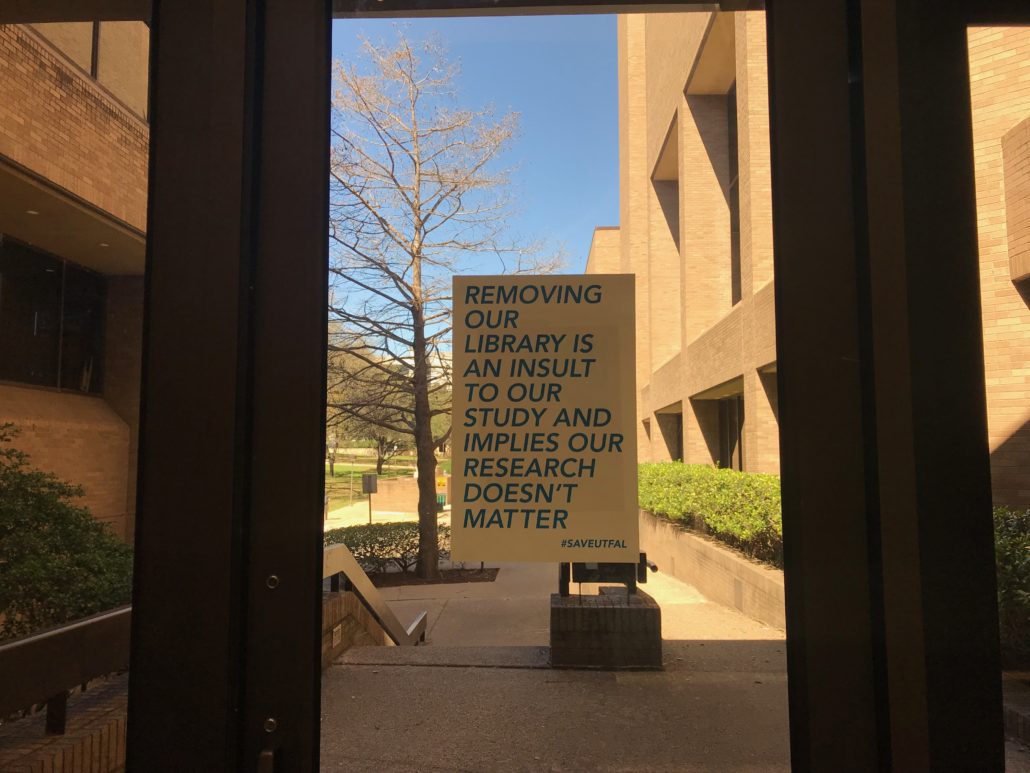

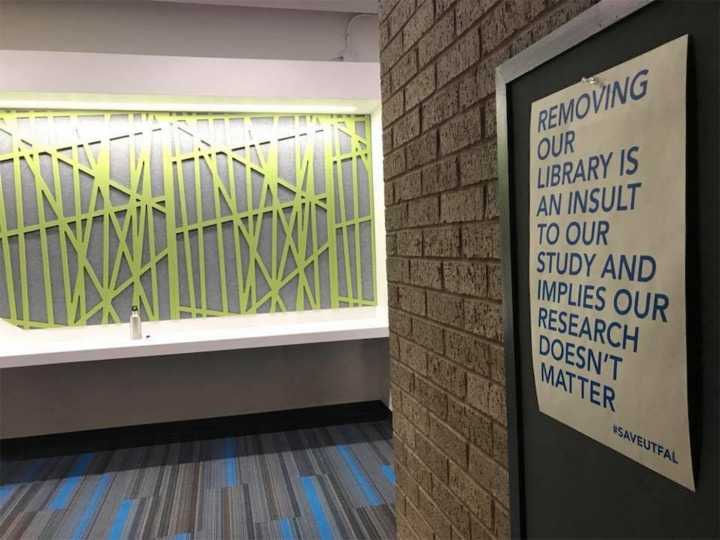

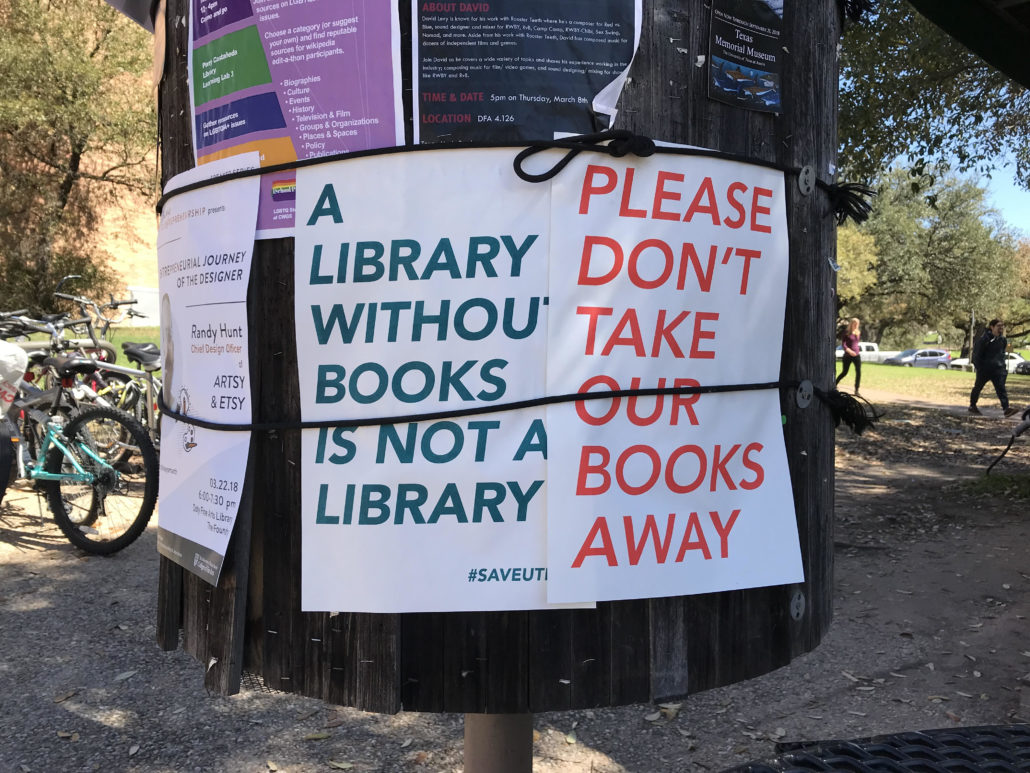

Certainly the University President as been at the focus of attacks on this plan to sell forty-six works from the Museum’s collection through Christie’s this spring. But take a look at the University Museum’s

Certainly the University President as been at the focus of attacks on this plan to sell forty-six works from the Museum’s collection through Christie’s this spring. But take a look at the University Museum’s

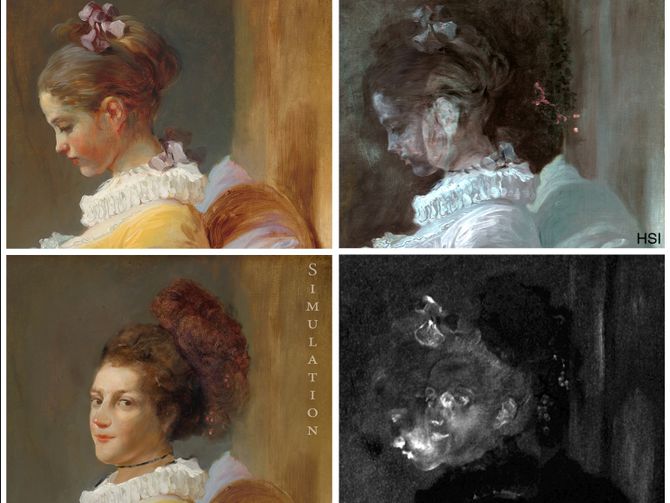

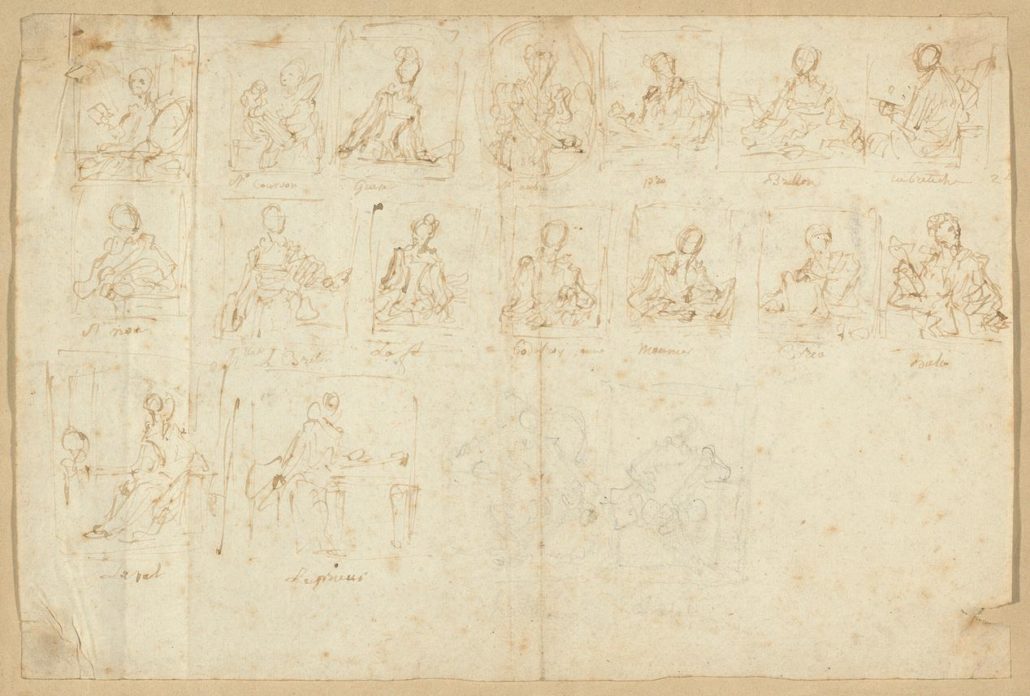

What is the investment value of examining the work with these custom-built tools? If the conservators today acknowledge the previously incorrect 1985 conclusion from conservators that a man’s portrait lay beneath the surface, how accurate will this new muddled image of a woman with a headdress askew be in concluding who from his circle Fragonard had originally intended to depict?

What is the investment value of examining the work with these custom-built tools? If the conservators today acknowledge the previously incorrect 1985 conclusion from conservators that a man’s portrait lay beneath the surface, how accurate will this new muddled image of a woman with a headdress askew be in concluding who from his circle Fragonard had originally intended to depict?