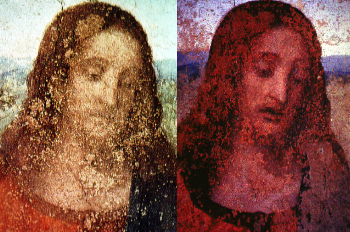

Sistine Ceiling, Before and After Restoration: Looking Back In Order To Look Forward.

Ruth Osborne

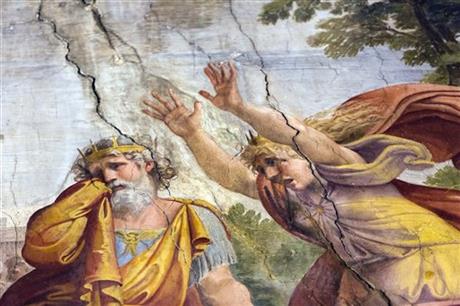

Several years ago, ArtWatch helped produce a film on the changes that occurred when the Sistine Chapel ceiling underwent restoration in 1980-1994.

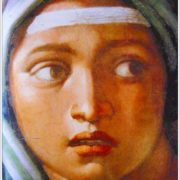

It considers the frescoes of Michelangelo Buonarroti before and after the massive restoration treatment. We would like to share with you some outtakes of the film that we believe may enlighten viewers to the importance of considering how a work is treated when restored, as well as paying attention to its care post-restoration. ArtWatch UK has recently provided studies on these new developments here and here. For the full film, click here: “ArtWatch: The Scandal Behind Art Restoration” (2005)

What is most compelling are the interviews of those who had seen the frescoes up-close and personal before 1980 – artist Frank Mason and writers Alexander and Jane Eliot. Have a look at the clip posted above, as well as the Eliots’ 1967/68 documentary The Secret of Michelangelo below, which provides unique coverage of the ceiling before treatment. Artists may not have been consulted before the 1980s-90s restoration, and no condition reports were done to address the particular needs and options for treatment. But now, though it’s taken 20 years, the artistic and broader public are now more aware of how significantly restoration can alter and damage a work of art irreversibly. Perhaps, with the current concerns over increasing atmospheric pollution, overcrowding, and visibility amidst deterioration, those responsible for this expansive work will reconsider such reckless techniques. For the book that takes an extensive look at this and other restoration damages, Art Restoration: The Culture, The Business, and The Scandal (1996), copies are available via our New York office or here.