Another Anniversary

James Beck

Timed to coincide with the 500th anniversary of the death of Andrea Mantegna (born c. 1431) in 1506, three Italian cities in which the artist executed some of his major works are hosting exhibitions in the artist’s honor: Mantua, Padua and Verona, each set to run from 16 September 2006 until 14 January 2007.

Mantua’s exhibition, Mantegna a Mantova: 1460/1506, will be held at Palazzo Te, Padua’s Mantegna e Padova: 1445/1460 will be held at the Eremitani Museum, while Verona’s Mantegna e le arti a Verona will be at the Palazzo della Gran Guardia.

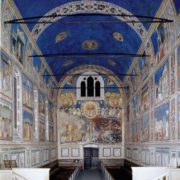

As is often the case with large blockbusters, the organizers have emphasized several opportunities for the visitor that make the show a must-see. It has already been announced that when the exhibitions end in January, the San Zeno Altarpiece in Verona, one of Mantegna’s most important works, will undergo an extensive two-year restoration campaign, making this the viewer’s last chance to see the work for the near future. The exhibition also offers the opportunity to see the Ovetari Chapel frescoes in the Eremitani in Padua, which were shattered into 80,000 small fragments following an airstrike in 1944. With the help of new computer software, they have been recomposed and will be on view as part of the anniversary celebrations.

In order to orchestrate the events, the Ministry for the Cultural Heritage and Activities created an 82-member National Committee (Comitato Nazionale per le Celebrazioni del quinto centenario della morte di Andrea Mantegna) composed of scholars and government officials. In a nearly unprecedented example of the mass-shipment of works of art, 140 museums and collections agreed to lend works of art by the artist and related masters, 352 of them in total. The website for the project calls the undertaking “a completely new type of exhibition” in terms of its scope, with each of the cities hosting not only their share of the primary exhibition, but numerous other related shows at secondary sites. On behalf of the exhibition, Alpitour is offering 2- and 3-day travel packages to all of the shows, for E135 and E245, respectively.

As in the case of most large exhibitions, the works are undoubtedly put at risk by their shipment. Some daunting statistics are offered on the exhibition’s website: The collective insured value of the works is E647,000,000, and fifty-five works were restored for the shows, with a total cost of E271,000. The exhibition also touts the obligatory “new discoveries,” such as the Madonna della Tenerezza, a formerly unknown painting in a private collection, which is annexed to the Padua show (on view at Palazzo Zuckermann).

Not all of the loans were easily acquired. Vittorio Sgarbi, President of the Mantegna Committee and curator of the Mantua exhibition, requested that the city of Bergamo loan Mantegna’s Madonna and Child, currently housed in the Accademia Carrara. Bergamo, which refused the loan citing the painting’s fragile condition, subsequently distributed 20,000 free passes for entrance to the Accademia to see the work.

Other loan requests by the organizers of the Mantuan exhibition were met with similar reluctance on the part of the institutions. The Brera Gallery in Milan refused to send Mantegna’s Dead Christ, also citing its delicate condition. Sgarbi claimed that the museum was “telling lies,” since the work had been shipped to Mantua in 2002 for another exhibition: “It is not possible for a work to have been in good condition four years ago, when it was loaned to Mantua, and ‘sick’ now. Someone is not telling the truth. We send troops to Lebanon, but not paintings to each other”. Despite pressure applied by Sgarbi, who claimed that the absence of the Dead Christ and the St. Sebastian from the Ca’ d’Oro would cost E1.6m in entrance fees, approximating that 200,000 fewer people would attend, the Italian Culture Minister and Vice Prime Minister Francesco Rutelli initially supported the Brera’s decision.

Sgarbi wrote an open letter to Rutelli:

“Dear Minister, Get them to tell you the truth. Brera will not loan us Mantegna’s Dead Christ and Ca’d’Oro refuses to give us the Saint Sebastian. The galleries are making it a health issue, saying that the paintings cannot be moved because they are unwell. Do not allow yourself to be bullied by deceitful officials: intervene so that we can have them”.

Sgarbi argued that the works were in a satisfactory condition, and therefore should be sent to the exhibition, but that if they were in fact that fragile, it was wrong to let them deteriorate further and his committee would fund their restoration.

Initially, Rutelli held his ground and did not overrule the technical judgment of Brera officials. The ministry defended the decision of the Brera, citing the unusual methods of the painting, which is tempera on canvas. Then, in August, Rutelli announced: “I approved that the Dead Christ of Brera be sent to the Mantegna exhibition in Mantua after an in-depth technical inspection. We have also made available some other works that were requested by the organizing committee and the city mayors, with the help of the Ministry. I feel that guidelines should be decided for loans and exhibitions, and that is why I have set up a Commission with a high scientific profile, in order to help requests be made with greater certainty.” Rutelli has since announced the formation of a Committee to establish official state guidelines for the lending of works of art.

Like the Brera, the Ca d’Oro in Venice also had objections to the lending of one of its Mantegna works, a Saint Sebastian. Their refusal was multi-faceted. First, they argued, the work was currently undergoing restoration, which could take an additional few months. Secondly, they argued that the museum’s collection was substantially diminished by its absence.

With anniversary exhibitions on the rise and an ever greater interest in more complete shows with more impressive loans, the Mantegna exhibitions in Mantua, Padua and Verona have set a very dangerous precedent. No longer will the fragility of an object be a hindrance to the loan of any work deemed critical for an exhibition, even if — or especially if — the need is a financial one.

The Institute, in collaboration with various research bodies (CNR laboratories, Fisbat in Bologna, CNR Institute of Chemistry and Technology of Radio-elements in Padua, CNR Centre for the study of art works in Rome, the Institute of General Chemistry at Venice University) therefore carried out a number of surveys between 1977 and 1979, aimed at discovering the causes and the mechanism behind the deterioration, in the light of research into the overall conservation history.

The Institute, in collaboration with various research bodies (CNR laboratories, Fisbat in Bologna, CNR Institute of Chemistry and Technology of Radio-elements in Padua, CNR Centre for the study of art works in Rome, the Institute of General Chemistry at Venice University) therefore carried out a number of surveys between 1977 and 1979, aimed at discovering the causes and the mechanism behind the deterioration, in the light of research into the overall conservation history.