Transparency and Neglect: Conservation on Display

Einav Zamir

“In the Artifact Lab: Conserving Egyptian Mummies” – an exhibition at the University of Pennsylvania that focuses on the process of conserving ancient artifacts. Courtesy: Past Horizons blog.

In what seems like a new trend to explore the world of art conservation through process-oriented exhibitions, the Blanton Museum of Art at the University of Texas at Austin, in conjunction with the National Gallery of Canada, opened “Restoration and Revelation: Conserving the Suida-Manning Collection” to the public on Saturday, November 17.

The exhibition focuses on the conservation efforts, including the cleaning and repainting, of several Old Master paintings and drawings from the museum’s Suida-Manning Collection, established in 1998. In a recent press release, the Blanton Museum stresses the potential for discovery, asserting that “new knowledge about the works and their makers” can result from restorations. However, the use of a reconstructive approach (repainting) in treating these objects suggests a greater interest in “visual integrity” than historical veracity.

Similar exhibitions, such as the University of Pennsylvania Museum’s “In the Artifact Lab: Conserving Egyptian Mummies,” create environments in which patrons can actually view restorations through a glass-enclosed conservation lab. The Ghent Altarpiece cleaning is also on display for public viewing. While it would seem that a certain degree of transparency is implicit in such demonstrations, thereby creating a sense of accountability, the effect is rather to heroicize art conservation and its practitioners.

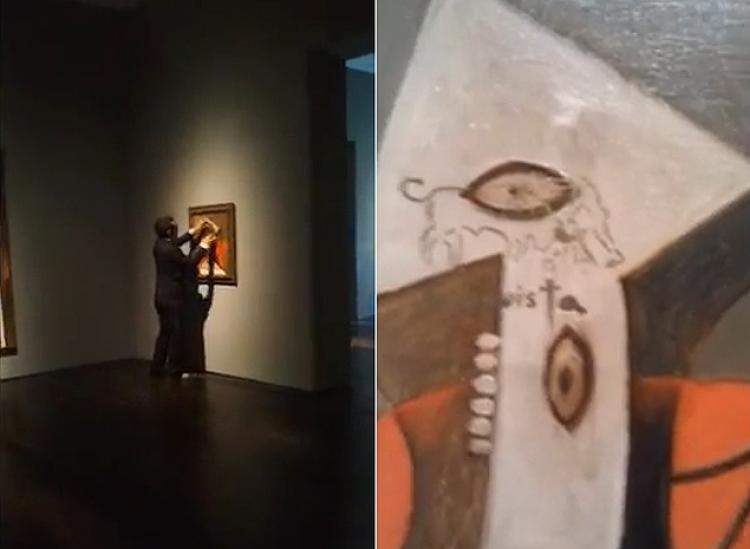

Antonio Carneo’s “The Death of Rachel” undergoing conservation treatment at the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, for the current exhibition “Restoration and Revelation” at UT Austin. Courtesy: UT Austin.

Perhaps a more fair and balanced approach to the many issues concerning the conservation of paintings, particularly those that have suffered severe deterioration, would produce an honest examination of the field overall. As James Beck and Michael Daley state in their book, Art Restoration: The Culture, the Business, and the Scandal, “The ‘science of restoration’, like all science, is not a monolithic cure-all.” If a museum rejects this reasoning, then questions regarding the moral implications of extensive repainting, and the museum’s obligation to its patrons to present clear delineations between original and contemporary components of any work, are otherwise wholly ignored. Any knowledge gained from such an exhibition is therefore tempered by what has been lost – the opportunity to develop a more informed audience, and therefore, a more critical public opinion.

“Restoration and Revelation: Conserving the Suida-Manning Collection,” is scheduled to run through May 5, 2013.