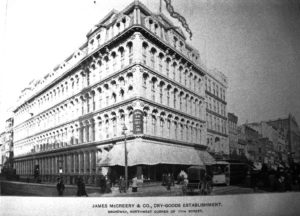

Donald’s Demolition: Reckless Jackhammering of Artistic Heritage to Make Way for the First Trump Tower.

Ruth Osborne

What to do with some iconic sculptures on the façade of a historic building that is being razed for a new glass tower?

Sculptures on the facade of the Bonwit Teller building, as it is prepared for demolition in 1980. Courtesy – Nathan Kernan / New York Times.

Well, you could remove them intact and give them to the museum just blocks up the street. Or you could forget about salvaging architectural remains altogether and just smash them along with the rest of the building. This is exactly what happened in 1980 when presidential candidate Donald Trump, then a 33 year-old real estate developer, appeared in the New York Times as the man responsible for destroying two Art Deco sculptures that had been promised to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

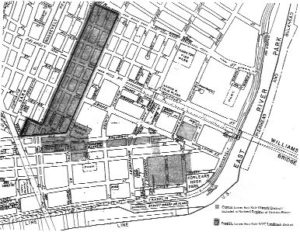

The pair of sculptures, along with some “gilded 20-by-30-foot grillwork of interlocking geometric designs” that framed the entrance of the 1929 Bonwit Teller department store that formerly stood on the corner of 5th Avenue and 57th Street in Manhattan, were jackhammered unannounced during demolition of the historic structure. In unrepentantly smashing the 15 ft tall stylized female nudes and nickel grillwork, Trump had, according to the then-Mayor’s office, failed at his “moral responsibility to consider the interests of the people of the city”. A Trump representative told the Times the next day “we don’t know what happened to it.” It was not until four days after the incident that a revealing statement was finally released, proving that Trump indeed called for the destruction of the sculptures and rare grillwork. According to Trump’s camp, this was due to the fact that the cost of their removal could have been more than $500,000 (though a few days prior, another representative had put the estimate at $32,000). Trump also tried to make this about the safety of pedestrians: “If one of those stones had slipped…people could have been killed. To me, it would not have been worth that kind of risk.” Was this really about pedestrians? Or was it about a few pennies being shaved off a $100 mil. project?

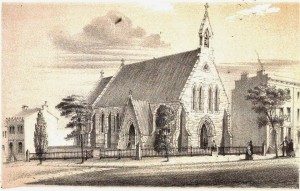

Bonwit Teller building in 1956. Courtesy: AP.

Bonwit Teller building 1950s. Courtesy: AP.

Trump had apparently already received tax abatements of up to 90% on some of his other development projects around the city. A New York Times article published just a few months after the event read: “Evidently, New York needs to make salvation of this kind of landmark mandatory and stop expecting that its developers will be good citizens and good.”

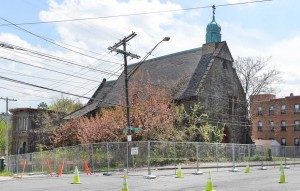

Trump Tower, completed 1983.

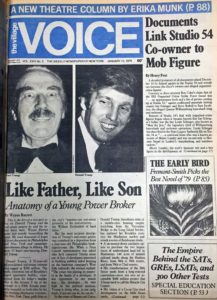

Donald Trump with his father Fred in Brooklyn.

From this early appearance in the media, Donald Trump has made for himself a reputation as a developer who skirts responsibility and commitment and instead places only the interests of his brand name and his company’s bottom line at the fore of his mind. Forget about the city that he’s impacting in the expansion of his empire – it’s his name that must go first. From reports of using illegal immigrant workers at the Trump Tower construction site in the early 1980s, to pushy donations to and questionable favor from city and federal officials, to violating regulations to build the Trump Soho in 2006 , he has proven himself unforgiving to any other interests around him.

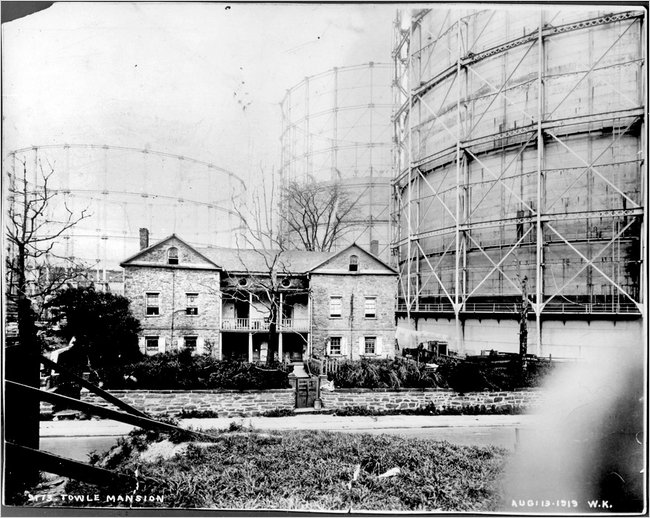

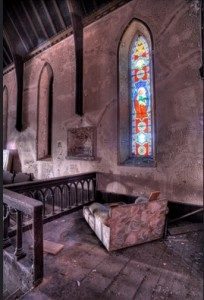

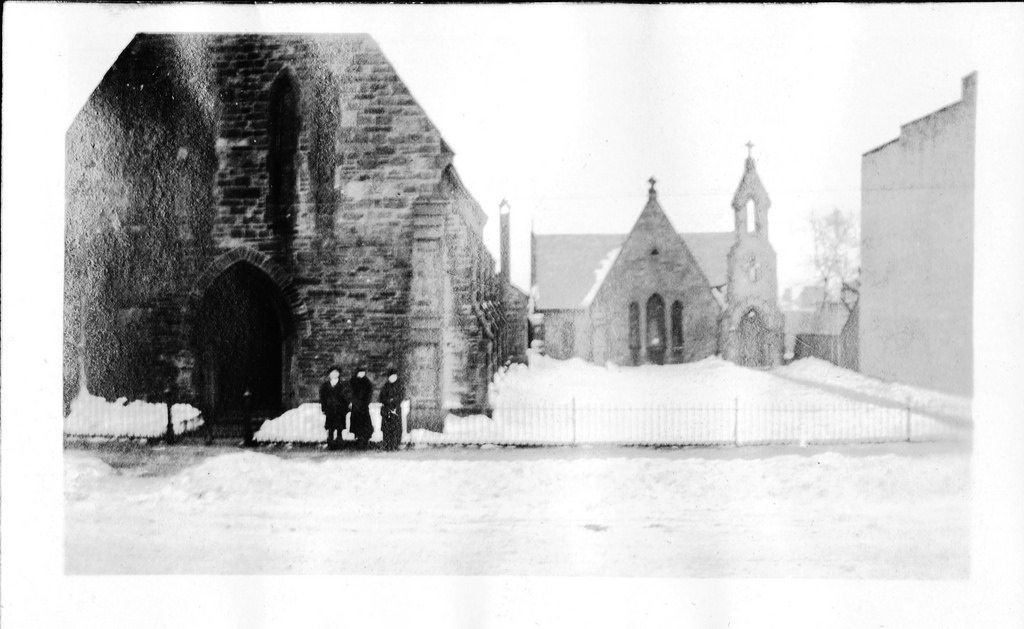

It’s no surprise, however, considering his father’s showy demolition of what would have been a landmarked site at Coney Island in Brooklyn – the “Steeplechase” – in 1964. The Trump disregard for art, history, and preservation is rooted back in the turbulent decade of the 1960s that created the uproar for the Landmarks Law in the first place. Fred Trump was then up against challenges from both the surrounding community and Chamber of Commerce and legal restrictions on development in an area zoned residential. At his “Demolition Party”, he decided that regardless of legal limitations he was still restricted under, it was his call to demolish the site himself. He reportedly encouraged guests to toss bricks into the Steeplechase Pavilion’s stained glass windows, and then proceeded to bulldoze the site to the ground later that night. Fred Trump’s reputation as a racist, profiteering developer is well documented, and his mark on south Brooklyn is the focus of a recently opened exhibition at the Coney Island Historical Society; it’s no surprise that his son couldn’t care less for an un-landmarked Art Deco building that was in the way of his namesake tower.

Fred Trump at his Demolition Party at Coney Island, 1964. Courtesy: Charles Frattini/NY Daily News Archive via Getty.

First in a two-part series, published in the January 15, 1979, issue of the Voice. Courtesy: The Village Voice.

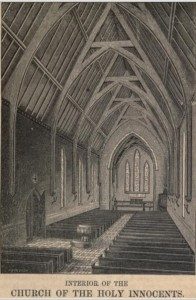

Joseph Kaminski’s piece on the Bonwit Teller building earlier this year provides an extensive description of the structure’s design from contemporaries. In 1929, American Architect magazine stated that the building was “a sparkling jewel in keeping with the character of the store”. More than fifty years later, Donald Trump’s representatives considered the building’s sculptures to be “without artistic merit”. Since then, he has made his opinions on art well known to the public.

Morris Adjmi, Founder & Principal, Morris Adjmi Architects

Morris Adjmi, Founder & Principal, Morris Adjmi Architects