Evidence of the Eyes: An Interview with Alexander Eliot

Einav Zamir

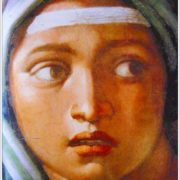

In the landmark 1967/8 documentary, The Secret of Michelangelo, Every Man’s Dream, Alexander Eliot, painter and former art critic and editor for Time magazine states that “almost everything we saw on the barrel vault came clearly from Michelangelo’s own inspired hand. There are passages of the finest, the most delicately incisive draughtsmanship imaginable.” The film, produced by Capital Cities Broadcasting Corporation, directed by Milton Fruchtman, written by Alexander Eliot and narrated by Christopher Plummer and Zoe Caldwell, provided a brief, one hour tour of the expansive Sistine ceiling. Through the use of close-ups, audiences were presented with details of the fresco never seen before, details that were impossible to grasp at great distance:

At the time, the film was both groundbreaking and immensely popular. Now however, it serves as a testimony to what has been stolen, through subsequent cleaning and restoration efforts, from the fresco’s original glory. Barely obtainable (there’s just one copy at the Central Michigan University Library in Mount Pleasant), and no longer broadcast on national television, The Secret of Michelangelo has become quite secret indeed.

I recently had the opportunity to speak with Alexander Eliot about the film, the chapel, and his fight against the cleaning, which began in 1981.

How are you connected to ArtWatch?

I’m all for ArtWatch. I was there at the beginning of it with Frank Mason and Jim Beck, and I think you’re really onto something very important.

What sort of evidence made you believe that the restoration was damaging the ceiling? How did you come to that conclusion?

It’s really the evidence of the eyes. Jane and I were up there on a tower that was built for us to research and write a one hour documentary on the ceiling years before the cleaning. The tower could be moved to bring us within touching distance of each section, over a six-week period.

That must have been an incredible experience. What kind of condition would you say the fresco was in while you were examining it?

Fabulous condition. There were some craquelures – it had cracks here and there, which happens naturally over the course of centuries, but the painting itself was all there. It was extremely subtle, rich, fresh, and pure – it was Michelangelo, and absolutely unbelievable. Jane [Jane Winslow Eliot, Alexander’s wife] first realized and pointed it out to me that the surface had mostly been done a secco (in the dry) because Roman fresco plaster goes porcelain hard within hours. So Michelangelo spent almost two years embellishing his quickly sketched under-painting.

And after the restoration?

They used a cleaning agent developed to wash stone exteriors. It took away all the a secco. What you see now is the under-painting. The conservators said “No, he just painted in the Florentine style, and on top is just a lot of glue-varnish, unknown hands, and dirt, and we need to remove it.”

How did you react? Was there an initial impulse to object?

Frank Mason said “We’ve got to protest and stop the cleaning” to which I responded “You can’t buck city hall, let alone the Vatican.” Then Frank said, “Yes, but think of how awful you’ll feel if you don’t try,” and so he recruited me. I then wrote a piece for Harvard Magazine on the subject, which Jim Beck told me helped persuade him to join us. At that point, the Vatican became noticeably upset.

Upset? In what way, and why?

Beck was such a prestigious figure, being a professor of Italian Renaissance art at Columbia University, so they hired a PR firm, a Madison Avenue outfit, to promote their ceiling scrub and make the three of us appear like childish, publicity seeking nut-cases. And they succeeded in that mission by inviting a number of VIPs – art critics, art historians, and museum directors – to come free of charge and take a look for themselves. They took them up on their comfortable scaffold with all their so-called “scientific equipment,” and even gave some a cloth to personally wipe off the accumulated “filth,” as they called it, from the painting. Instant experts were made that way, and simultaneously hooked.

So there was support from the academic community for the cleaning – who were some of its advocates?

Thomas Hoving was one; A previous director of the Metropolitan Museum and then editor of Connoisseur Magazine. Robert Hughes, Art Editor of Time Magazine, as I had been for fifteen years, was another. He wrote in his last book before he died that seeing Michelangelo’s cleaned work ‘the way he painted it’ from the restorers scaffold was the most vivid experiences of his whole 50 years as an art critic. It’s really too bad. The cleaning went on for years and years and they destroyed the thing.

And what about the film you produced? Is it still available to those who wish to view the ceiling as it was before the cleaning?

Unfortunately, I don’t have the rights to the film, so in that sense, it’s not available. For years it was rebroadcast on holidays by ABC. It was a TV success at the time.

And now, after so much time, with the evidence supporting your position so abundant, are there influential people out there that still applaud the cleaning?

People don’t like to admit that they were mistaken, but by now everybody in the art community knows that we, Jane and I, Jim Beck, Frank Mason, and Michael Daley, were right.

Do you think the Vatican should restrict tourism in order to preserve what’s left of the fresco?

They would never restrict visitation – they make too much money from it. It was all about money to begin with. They wanted to make a big publicity stunt in the first place, make it more “accessible to the public,” and beef up tourism. As long as they’re making money off of it, they’re never going to restrict access.

What do you think can or should be done to prevent further degradation?

It doesn’t matter what I think or believe. They’ve lost the picture already. The under-painting, the concept, is still there, but the painting is gone. It’s been scrubbed away with chemicals. They can’t do anything significant to save what’s left, either. Maybe they’ll apply some pseudo-scientific hocus-pocus, but they won’t reduce the influx of tourists.

At the conclusion of our conversation, while coming to grips with the grim reality of the circumstances, I asked Eliot if he believed the Vatican would ever admit its guilt in this crime against our cultural heritage, to which he responded with a memory. He spoke of a time when Fabrizio Mancinelli, Curator of Painting at the Vatican, spoke to him regarding the highly debated restoration:

“I respect your opinion Mr. Eliot, and I trust that you’ll respect mine.”

To which Alexander Eliot, the man who once stood mere feet below the magnificent fresco, responded:

“You and I don’t matter, but the Holy Father will go down in history as the destroyer of the world’s greatest painting.”

For more on Alexander Eliot and his writings, please visit:

http://alexandereliot.com/about/

Eliot, Alexander. “Save Sistine From the ‘Restorers'” Los Angeles Times 20 Sept. 1987: 5.

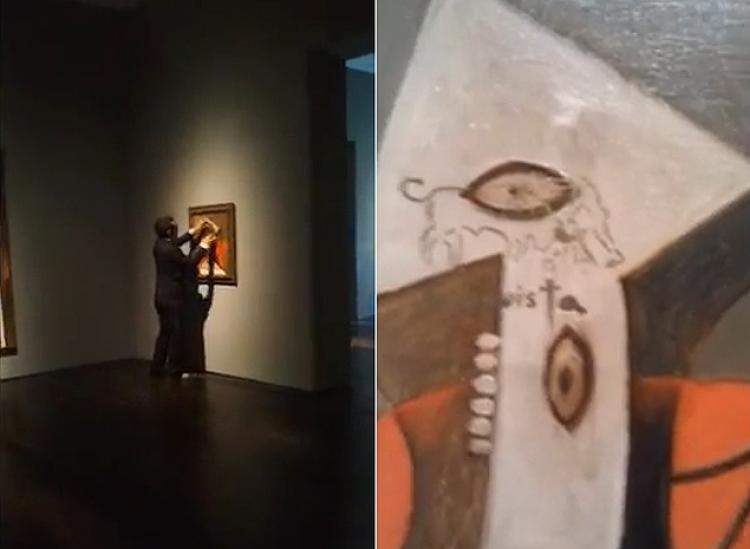

However, in recent years there has been a tremendous amount of damage done to art objects that are even more difficult to protect, either from thieves, mentally-ill vandals, or just rowdy individuals. Public monuments, both architectural and sculptural, that are outside of the considerably safer museum environment, are more difficult to safeguard, even with the increasing presence of security cameras. Italy’s fountains are seemingly impossible to protect. In 1997, the Neptune fountain by Ammannati was vandalized twice, with the second incident resulting in the breaking off of one of the horses’ hooves. The city had recently installed eight remote control television cameras, though their view was obstructed by scaffolding. That same year, Bernini’s Four Rivers Fountain in Rome’s Piazza Navona was damaged when three men climbed onto the statue and broke the tail of a sea-serpent. (One of the perpetrators vowed to sue the city over damage to his foot incurred during the incident).

However, in recent years there has been a tremendous amount of damage done to art objects that are even more difficult to protect, either from thieves, mentally-ill vandals, or just rowdy individuals. Public monuments, both architectural and sculptural, that are outside of the considerably safer museum environment, are more difficult to safeguard, even with the increasing presence of security cameras. Italy’s fountains are seemingly impossible to protect. In 1997, the Neptune fountain by Ammannati was vandalized twice, with the second incident resulting in the breaking off of one of the horses’ hooves. The city had recently installed eight remote control television cameras, though their view was obstructed by scaffolding. That same year, Bernini’s Four Rivers Fountain in Rome’s Piazza Navona was damaged when three men climbed onto the statue and broke the tail of a sea-serpent. (One of the perpetrators vowed to sue the city over damage to his foot incurred during the incident).