Fragonard’s Layers & the Promotion of Conservation Treatments

Ruth Osborne

X-Rays. Lasers. Multi-Spectral Imaging. We’ve posted on these before: how newly developed technologies like the Er:YAG laser are promoted with such “promising” results, despite persisting doubts from other conservation professionals as well as publications on the risks of its application.

At ArtWatch UK, past coverage has highlighted the business interests involved in conservation technologies as the field finds new ways of convincing the public of the importance of new treatments.

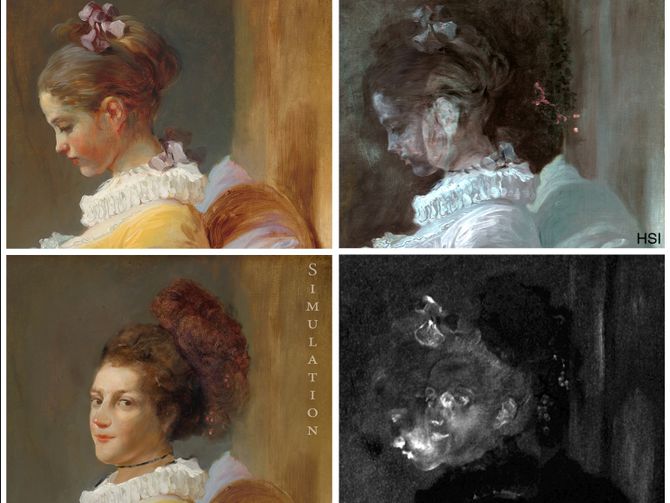

The latest work of art to be put through the ringer – or, rather, a “custom-built…high sensitivity near infrared hyper spectral imaging camera and an x-ray fluorescence (XRF) imaging sensor” is Young Girl Reading by Jean Honoré Fragonard. On this painting, a team of three at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. also used high-res color photography, reflectance imaging spectroscopy (or IRS), reflectance transformation imaging (or RTI), and mercury analysis alongside the previously-mentioned XRF imaging.

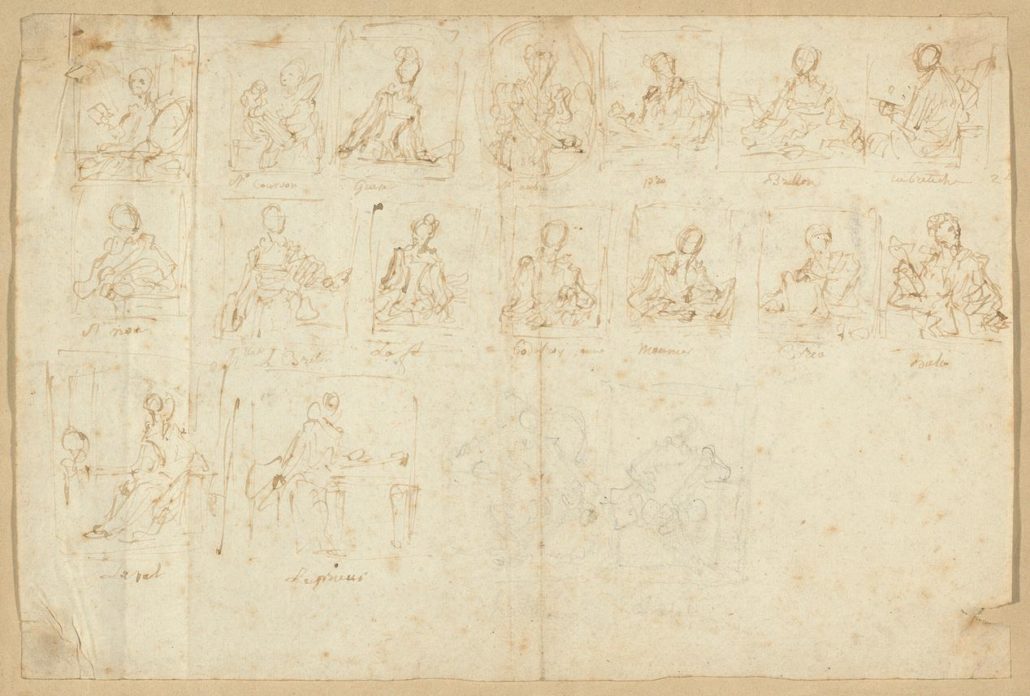

Jean Honoré Fragonard, “Sketches of Portraits” c. 1769. Courtesy: National Gallery of Art / Wall Street Journal.

The team of a senior conservator, imaging specialist, and paintings expert at the NGA insist that this recent treatment was to discover more about Fragonard’s intriguing “fantasy figures” (portraits of his opulent social circle in masquerade style) and their connection with this finished work of a girl reading. A recently identified page of preparatory sketches by the artist discovered at a 2012 Paris auction. And that these sketches included one for Young Girl Reading in its originally intentioned form. That’s all very interesting. But beyond setting the newly-discovered preparatory sketch side-by-side with the painting in question, what more is actually being uncovered about Fragonard’s fantasy figures, especially if the artist himself decided not to paint her in the first place? And if the sketch does not feature a name underneath, pointing to the potential original sitter or patron?

What is the investment value of examining the work with these custom-built tools? If the conservators today acknowledge the previously incorrect 1985 conclusion from conservators that a man’s portrait lay beneath the surface, how accurate will this new muddled image of a woman with a headdress askew be in concluding who from his circle Fragonard had originally intended to depict?

What is the investment value of examining the work with these custom-built tools? If the conservators today acknowledge the previously incorrect 1985 conclusion from conservators that a man’s portrait lay beneath the surface, how accurate will this new muddled image of a woman with a headdress askew be in concluding who from his circle Fragonard had originally intended to depict?

Courtesy: Mandel Ngan / AFP.

We’ve reached out to the National Gallery of Art conservation studio on the motivations behind, and future intentions of, the treatment of the art. They have not yet responded, despite multiple attempts. We’ve also asked for more detailed information on how the new custom built machinery was used to achieve the views of the woman facing forward beneath Young Girl Reading. How helpful were previous studies in revealing the, now reportedly truer, underlayer? It was reported that the NGA team used a tiny cross-section taken from the painting from around the time of the 1985 restoration on the work. But just how did all the new the x-ray fluorescence and spectroscopy imaging tools enable them to see the final underlying image? What was the hope behind investing significant funding into these new conservation tools? After all, members of the NGA team are quoted as saying “It was not a painting about which we imagined making further discoveries” and “You start off this research not knowing what you’re looking for”.

Editions Braun & Cie. (French, 19th/20th Century), After Jean-Honoré Fragonard (French, 1732-1806) Stamped “…Editions Braun et Cie” on the reverse, inscribed “Braun…” in ink on the stretcher. Photo-mechanical reproduction on paper laid on canvas, 22 1/4 x 16 in. Courtesy: Skinner Inc. Auctions, July 2011.

As for known extant copies of the work, there are several, but all from after the late nineteenth century, so far as we have found. And all which celebrate the finished image of the unidentified girl reading, none that hint at any layers beneath.

Just to give a further sense of how greatly media outlets work to increase public intrigue in conservation science…

Reports also make mention of the inscriptions beneath the sketches identifying either a sitter or patron of the fantasy figure portraits, though the sketch made for what turned out as Young Girl features none. So, in fact, they have failed to point out just how these new “findings” identifying sitters are at all related to Young Girl Reading.

According to the reporter for AFP, “NGA experts used techniques akin to those NASA deployed on its Mars rovers to dispel any doubt the work belonged to a boldly experimental series by a young Fragonard.”

…and the new claim:

“Yet more discoveries possibly await”.

This is how the article ends.

A recent review through Forbes even likened the use of laser examination of this piece to the work of encouraging connoisseurship in today’s art world:

In the age of social media, connoisseurship has often been reduced to “likes.” Fad and fashion permeate the 21st century art market, where there is rare justification for greatness. Exhibitions like FRAGONARD: The Fantasy Figures require the museum-goer to reconsider the history and context of art making. New technologies unmask details, propel connoisseurship…

Exactly how do they propel connoisseurship? Isn’t it the desire for new “discoveries” – and more museum visitors and funding – the reason these new technologies are so prominently highlighted in exhibitions? There is a whole history to this work to be considered and learned from – things like Fragonard’s studio sketches and the painting’s ownership history – but is this highlighted by the press? Clearly there is some confusion as to what “connoisseurship” entails.

The exhibit at the National Gallery of Art runs through Dec 3rd, 2017: https://www.nga.gov/exhibitions/2017/fragonard-the-fantasy-figures.html