A Different Era of Historic Preservation: Will New York Landmarks Law be able to last another 50 years?

Ruth Osborne

As the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission celebrates fifty years this month, it seems a pertinent time to consider the impact of this organization on the city’s landscape and its effectiveness in preserving the many histories of New York.

In response to the devastating destruction of Penn Station in 1963, the LPC and Landmarks Preservation Law were established in 1965 to provide a legal advocate for aesthetically and historically important sites and structures that make up the multi-layered character of the city. Since then, there have been wins and losses, demonstrating the necessity of such a law to protect New York’s history from complete disregard by the vested interests of developers and even politicians. Substantial numbers have arisen in the form of community and preservation groups now able to better protect the city’s heritage.

Proposed Frick Expansion. Courtesy: Neoscape Inc./The Frick Collection.

But it seems even the caretakers of a landmarked building can hold the potential to put its historic character in danger. In recent months, the Frick’s newly-announced expansion has raised many eyebrows, including those of former Frick director Everett Fahy. Their proposal, announced last June, would add a 106 ft tall addition (equivalent to ten-stories) above its landmarked 1913-14 building by Carrère and Hastings. It would also require the removal of the small 70th St. garden by distinguished 20th century landscape designer Russell Page and its accompanying Reception Pavillion with large windows onto the garden. The group Unite to Save the Frick has formed in response to what they deem a “destructive proposal,” stating their aim to “[preserve] the signature residential character that makes the Frick such a unique place to experience art…We urge the Frick to honor its own tradition of thoughtful additions and explore the many reasonable alternatives that exist for thoughtful expansion and modernization.” They have collected several artists, architects, historians, museum professionals, college deans, and others involved in the governance of various organizations committed to art and preservation. This long list includes former commissioners of the NYC LPC and the NYC Parks Dept., the founder of the Central Park Conservancy, and several other entire groups that have proven their strength in fighting for and funding preservation in New York. Does this sound like a group of advocates who would be denied a listening ear?

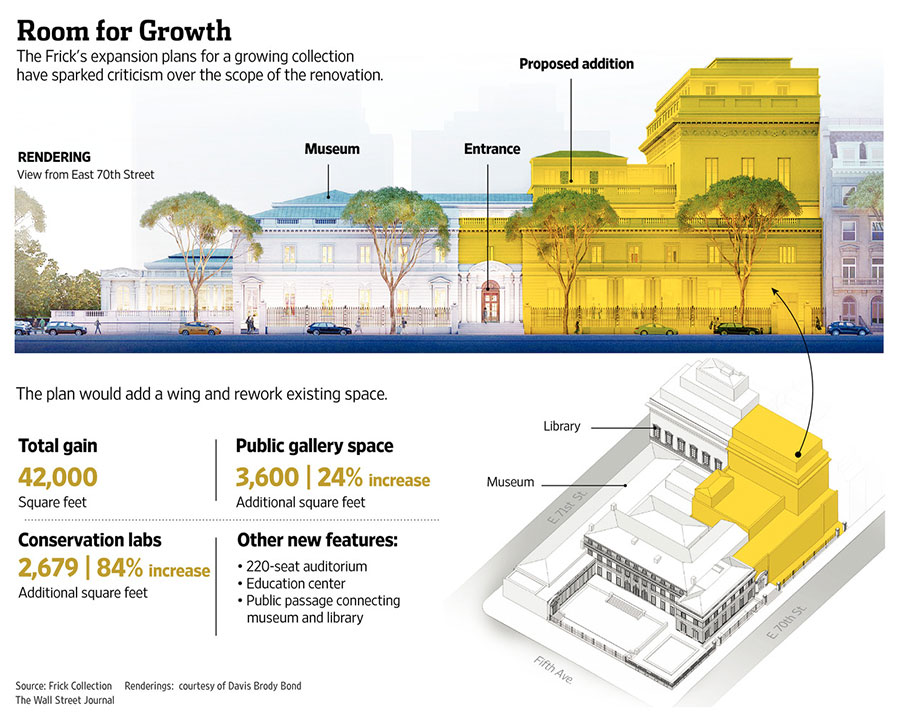

Proposed Frick Expansion (showing original and new sections). Courtesy: Wall Street Journal.

But this seems to be happening as the stewardship of cultural landmarks yields to the modernization of museum collections into giant conglomerates. Why must blockbuster exhibitions – which leave lines wrapping several times around the block – be the reasoning behind transforming this private domestic house museum into one with expansive conservation labs and more gallery space? Did Frick intend it as a museum of his artful interiors? Or as a second Met? The fall 2014 press release by current Director Ian Wardropper stated the “exciting plan” will allow the Frick to “now provide the amenities of a twenty-first-century museum.” It reads more like an advertisement for a hotel or apartment renovation than for a museum.

In a recent interview with the the Observer, architect Charles Warren maintains that this proposed addition is in no way a “modest” alteration to the building. Warren, a strong supporter of the United to Save the Frick group, presents a reasonable argument against the changes, despite preservation advocates often being portrayed as having an extreme or unrealistic mindset: “I’m not one of those people who wants to stop time, this isn’t [Colonial] Williamsburg, but is this needed?” Journalist Nate Freeman reminds readers that “several – if not nearly all – recent museum renovation projects have been over-budget and unsuccessful.” The Frick has still failed to make public even a rough estimate for the cost of the expansion. And while Wardropper insists that these changes are in the interest of creating “ample space” and an “expanded shop” for the Frick’s “growing constituency” and “new educational programs,” as well as opening up the second floor to visitors, the plans by Davis Brody Bond will add only 24% more public gallery space compared with the additional 84% increase in conservation lab space. It will also add another hill of limestone on top of a neighborhood gasping for green space.

Garden at the Frick by Russell Page (1977). Courtesy: Wall Street Journal.

We still await the Frick’s proposal to land on the desk of the Landmarks Preservation Commission, which should happen any day now. In the meantime, we encourage you to consider just how this will impact the nature of the collection and what precedent this sets for historic house museums and the historic landscape of the city at large. Is there a case for protecting smaller museums against becoming swallowed up by sprawling institutions with billion-dollar endowments? Similar questions arose with the repurposing of the the Corcoran Gallery in D.C. as it entered new ownership recently. Will landmarked sites no longer be able to preserve the very memory they were landmarked for in the first place?

Marion True, former curator of antiquities at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles [Fig. 2], once hailed as the “heroic warrior against plunder,” [1] was indicted in 2005 for violations against Italy’s cultural patrimony laws.[2]

Marion True, former curator of antiquities at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles [Fig. 2], once hailed as the “heroic warrior against plunder,” [1] was indicted in 2005 for violations against Italy’s cultural patrimony laws.[2]