The Cause of Preservation in the Valleys of the Kings and Queens.

Ruth Osborne

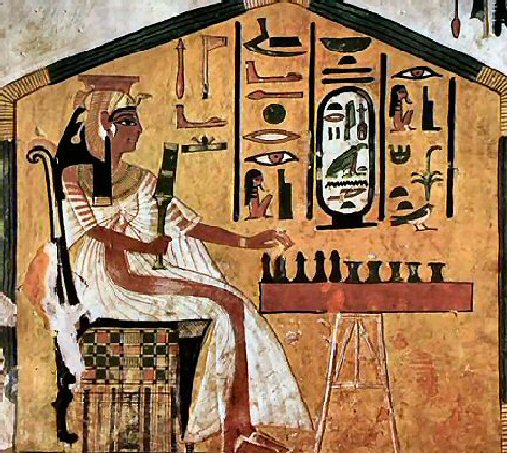

Painted wall showing Queen Nefertari playing senet. Courtesy: G.E. Wood.

The tomb of Queen Nefertari (13th century B.C.) has been referred to as the “Sistine Chapel of Ancient Egypt” for its fantastically well-preserved wall paintings.

Since its 1904 discovery in the Valley of the Queens by Ernesto Schiaparelli, the tomb has, like many artistic treasures, been exposed to the ravages of vandals and much environmental damage. It wasn’t until 1933 that access to the tomb was first restricted. The Art Newspaper recently reported that the tomb will now be re-opened once a month, despite it having been closed to visitors in 2006. Before that, the tomb had been restricted to a very limited number of guests after the conservators from the Getty worked for several years to stabilize the brilliantly preserved wall paintings.

This past April came the proud announcement of its re-opening for the 110th anniversary celebration of its discovery. As the press release on the Egyptian Tourism Authority’s website states, there were “several Italian archeologists” who attended. No doubt, these professionals served to allay any fears of the tomb being mistreated by those who should know best. Reluctant Minister of the ETA, Hesham Zaazou, is reported to have said the re-opening will have “an important impact on promoting cultural tourism in order to assure stability and security were restored in Egypt.” So, a piece of ancient heritage that has preserved the artistic traditions of those who built Egypt thousands of years ago will be subservient to the need to restore stability to the terribly torn modern nation? For the sake of renewing the inflow of income from visitors to the tomb? Surely the irony does not fall on deaf ears here – risking an already at-risk piece of ancient artistic and cultural heritage for the sake of making money off it? Where does this money then go – to the maintenance and preservation of the site? Will its needs for preservation not then increase precisely due to the fact that it has been opened again?

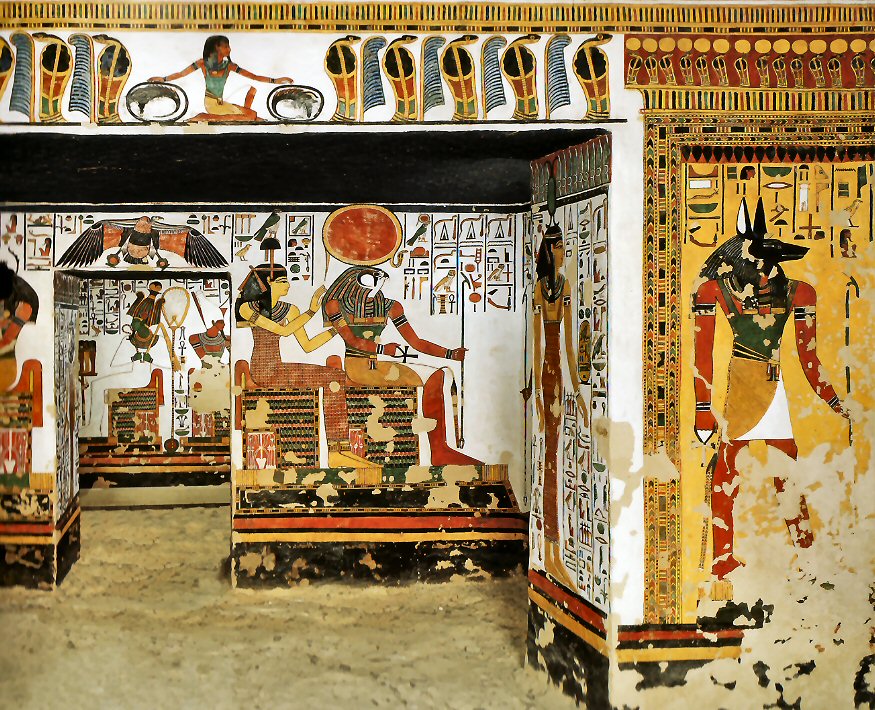

Antechamber (east wall), Vestibule, and access route to Lateral Chamber of Tomb QV66. Courtesy: G.E. Wood.

In the late 1980s, emergency methods had to be utilized by the Getty Conservation Institute in their attempt to secure the wall paintings from further eroding. The condition, analysis, and treatment are outlined in a report from conservator Frank Preusser, presented at the 1987 symposium on The Conservation of Wall Paintings organized by the Courtauld and the Getty. According to this report, conservators and scholars had worked for nearly five decades to determine the optimal solution for preserving the wall paintings.

Following the emergency treatment, the tomb was reopened in 1995 for about 10 years to only 150 visitors because of the continued risk of exposure to increased humidity, carbon dioxide, and microbiological activity from humans. The Getty even produced a large colorful volume meant to share the beauties of the tomb as a “descriptive walk-through…while conveying a strong message regarding the need for conservation and continuous monitoring to ensure the long-term survival of the tomb’s paintings.” It was at this same symposium that concern over the appropriate levels of cleaning for the Sistine ceiling was addressed.

Factum Arte working on color-matching in Tutankhamun’s tomb, 2009. Courtesy: Factum Foundation.

Factum Arte’s recently finished project with the popular tomb of Tutankhamun stands in stark contrast to the treatment of Nefertari’s tomb. Work began on this tomb in view of celebrating the 90th anniversary of its opening in 1922. Not yielding to the pressures of dwindling state coffers, the EU and Minister Zaazou, who is mentioned above, enlisted the help of Factum Arte in 2009 to study, scan, and recreate the tomb’s artwork with three-dimensional printed facsimiles. Not only did the project battle ongoing damage from human contact, but also previous conservation attempts in the tomb. Unfortunately, Tutankhamun’s tomb is one of the many art works that has suffered from eager but insufficient treatment before better methods are developed.

BBC’s coverage of Factum Arte’s facsimile questions its effectiveness in terms of the tomb’s preservation, due to the site’s continuous popularity with international visitors: “…years of visitors trekking around the old tombs of the pharaohs is causing these historic sites to deteriorate…but will tourists really want to travel to Egypt just to visit a mock-up?” However, while the facsimile has been completed and delivered to Egypt, it remains to be installed and utilized for protection of the original site from further deterioration. According to one tourist interviewed by the BBC: “We need to have that passion to see the real thing. If you’re seeing a replica, you don’t have that same passion.” But is it really authentic if it has been destroyed by years of exposure and bad conservation attempts? These sites simply weren’t made thousands of years ago for this kind of exhibition. Can Egypt’s Tourist Authority manage to see the things in a greater perspective and care for the long-term well-being of their cultural heritage?

According to artist Adam Lowe, founder of Factum Arte, “How works of art were looked after and protected in the past reveals how they were seen and valued…The same is true about the way we care for things now. To future generations it will reveal a lot about us – assuming we have not destroyed most of the things we inherited.”

Egypitian Minister Zaazou has expressed hope that the recent re-opening of other new ancient sites over the past several years will help double tourist revenue back to where it was before the 2011 revolution. This included the reopening of the pyramids at Giza in 2012. However, this followed on the heels of a series of stolen antiquities from museum collections and reported break-ins at archeological sites.

Meanwhile, Egypt is not alone in its problems caring for important ancient cultural and artistic sites. In Peru, Chan Chan – the largest pre-Columbian city in South America – faces the possibility of losing its UNESCO World Heritage site title (since 1986). This has developed with mounting damage to the archeological site due to lack of proper monitoring of visitors and nearby construction.

Since 2009, the Getty has committed to a new conservation effort at Tutankhamun’s tomb, working in partnership with the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA). One of the main goals is for their collected data to update recommendations for better use and safer preservation of the site during visitation and commercial filming and photography. Though researchers have apparently found that “the condition of the paintings is excellent,” their assessment of the tomb’s use relates an urgency to improve the wider public’s understanding of their impact on ancient heritage sites and why conservation is necessary. Putting into effect the Getty’s recommended changes to the site’s infrastructure and presentation would involve improving the areas open to visitors and the numbers that are allowed in.

All of this is part of a larger project to help better manage the visitation to and preservation of the site at the Valley of the Kings and Queens. The questions still remain, however, as to when, how and to what effect will these improvements in management of important cultural sites be implemented. This ultimately is up to the Egyptian government, and we hope they make the right decisions.

Egyptian Tourism Authority website.

Sources:

“Celebrating Nefertari’s tomb discovery to take place in Luxor,” Egypt Tourism Authority: News. 18 August 2014. http://en.egypt.travel/news/id/416 (last accessed 8 January 2015).

“Chan Chan at risk of losing ‘Cultural Heritage’ title.” IIC News in Conservation (December 2014) p. 4. https://www.iiconservation.org/system/files/publications/journal/2014/b2014_6.pdf (last accessed 8 January 2015).

Christopher Torchia, AP. “King Tutankhamun’s Stolen Dad Found; Egypt Sites to Reopen on Sunday.” ArtDaily. February 2011. http://artdaily.com/news/45106/King-Tutankhamun-s-Stolen-Dad-Found–Egypt-Sites-to-Reopen-on-Sunday#.VKIoucACEA (last accessed 8 January 2015).

“Conservation and Management of the Tomb of Tutankhamen.” The Getty Conservation Institute: Current Projects. Last updated March 2013. http://www.getty.edu/conservation/our_projects/field_projects/tut/scientific.html (last accessed 8 January 2015).

Conservation Perspectives (Vol. 23, No. 2, Summer 2008). The Getty Conservation Institute. http://www.getty.edu/conservation/publications_resources/newsletters/pdf/v23n2.pdf (last accessed 8 January 2015).

“Egypt reopens Pyramid of Chefren to tourists.” BBC News (11 October 2012). http://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-19912940 (last accessed 8 January 2015).

“Facsimile of the Tomb of Tutankhamun,” Factum Foundation: Projects. http://www.factumfoundation.org/ind/40/Facsimile-of-the-Tomb-of-Tutankhamun (last accessed 8 January 2015).

Florence Hallett, “We Made It: Factum Arte.” The Arts Desk: We Made It. 19 December 2014. http://www.theartsdesk.com/we-made-it/we-made-it-factum-arte (last accessed 8 January 2015).

Frank Preusser, “Scientific and Technical Examination of the Tomb of Queen Nefertari at Thebes,” in The Conservation of Wall Paintings: Proceedings of a Symposium organized by the Courtauld Institute of Art and the Getty Conservation Institute, London, July 13-16, 1987. http://d2aohiyo3d3idm.cloudfront.net/publications/virtuallibrary/089236162X.pdf (last accessed 29 December 2014) 1-12.

Garry Shaw, “Egypt reopens tomb as tourism falls,” The Art Newspaper: Conservation. (Issue 263, December 2014). http://www.theartnewspaper.com/articles/Egypt-reopens-tomb-as-tourism-falls/36357 (last accessed 8 January 2015).

Husni Mouafi, “Egyptian tourism minister looks to future,” Al Monitor. 9 January 2014. http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/business/2014/01/egypt-tourism-comeback.html (last accessed 8 January 2015).

Liz Jobey, “Conservation: Factum Arte remaking history,” FT Magazine (26 July 2013). http://www.ft.com/cms/s/2/b851d86c-f4c3-11e2-a62e-00144feabdc0.html (last accessed 2 January 2015).

“UNESCO volunteers working on Chan Chan conservation.” Peru This Week: Archeology (8 July 2014). http://www.peruthisweek.com/news-unesco-volunteers-working-on-chan-chan-conservation-103440 (last accessed 8 January 2015).

“Will a mock-up of Tutankhamun’s tomb pull in tourists?” BBC News: Fast Track (21 January 2013). http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/programmes/fast_track/9786255.stm (last accessed 8 January 2015).