Review of Art Law in 2013: Forgeries, Greed, and 70 year-old Wrongs to be Set Right

Ruth Osborne

Several interesting issues in the realm of art law came up in the last year. These will carry over new precedents into 2014 that will impact the field’s future. The following is a brief review of what 2013 brought under the ever –alert ArtWatch, and what this might mean for artistic and cultural heritage in the near future.

Knoedler Gallery, closed in 2011. Photo: The Art Newspaper.

In New York, new coverage appeared on the Knoedler gallery’s sale of forged abstract expressionist works. Beginning in 2011, the famed 165 year-old art gallery had shuttered its doors due to allegations of sold forgeries. Beginning in 2007, lawsuits for sales of fakes began with a Pollock and Motherwell and have continued with federal investigation into possible forgeries of de Kooning, Rothko, and other abstract expressionists. Testimonies and court documents trickling in over the last few years have brought out the names of other leading art galleries involved in similar sales. As The Art Newspaper reports, the uncovering of the Knoedler fakes reminds us of the deep underlying problems of authentication in the business of art. This speaks to the ever-increasing, and ever more apparent, level of greed tainting the art market. As Jack Flam, President and CEO of the Dedalus Foundation (founded by Robert Motherwell), states, “Without courage, honest and open communication, forgeries will distort art history and pollute the market.”[1] While the temptation may be great to follow after the profits of a promised art treasure trove, inaccurate authentication can also lead greater losses. In this case, it has resulted in the closing of a once-trustworthy international art dealership that supplied some of the greatest collections in the last two centuries.

It is the great shortfall of the world of art dealing that, when the market is strong and collectors are trusting, deception is more like to creep in. Collectors have millions to spare, and find themselves more likely to be duped. The temptation to cut corners is certainly greater in periods like these when the number of potential buyers is greater than the number of salable artworks. The surge of forgeries in the art market has also made art historians much more wary of consulting on authentication. When pointing out a fake could lead to a lawsuit, and with an influx of fakes on the market, connoisseurs are more and more hesitant to utilize their deep knowledge base for authentication. As Danielle Rahm (Director and Senior Appraiser at New York Fine Art Appraisers) reports in Forbes, several artist estate foundations dedicated to cleaning the art market of fakes have suddenly stopped authenticating because they have learned this comes with rather burdensome legal fees. She also points out the lack of objectivity amongst authenticators working with art dealers who are in the business of keeping competing works off the market: “Expert opinions regarding art used to be opinions rather than leverage in legal battles, so its little wonder that authenticators are heading for the hills.”[2]

Wolfgang Beltracchi in court in Cologne & a painting supposedly by German Expressionist Heinrich Campendonk. Photo: Vanity Fair.

The issue of authentication has also been touched on in recent years with the Beltracchi fakes scandal. Werner Spies, the German art historian who examined a supposed Max Ernst forged by Wolfgang Beltracchi, was the accidental supplier of certificates ensuring the works’ authenticity for interested buyers. As Spiegel reported, “Authorities estimate that the sale and resale of the artwork resulted in total losses to the art community amounting to nearly €34.1 million.”[3] Beltracchi, it seems, was himself the ringleader in an entire group that circulated forged German expressionist works around the world to internationally-renowned galleries and collectors. Sales of forged Beltracchi have entangled, among others, New York dealer Richard Feigan and German auction house Kunsthaus Lempertz.[4] As the owner of the Lempertz has found after investing tens of thousands of euros into x-ray machines to test against forgeries, science only goes so far: “[it] only [helps] if the forger used the wrong pigments in terms of date…In the end, you need to ask the experts.”[5] Once again, it seems science is still not the highest measure of proof for authenticity. As ArtWatch UK has pointed out is the case with the Bowes Museum public restoration of a secure Turner painting, scientific analysis still leaves a few questions lingering with regard to restoration treatments.

Our New York colleagues at the Center for Art Law have remarked on the steady stream of fakes being discovered in major galleries, museums, and even exhibitions. In order to protect boards of art experts, increasingly at the risk of shutting down,[6] the New York City Bar Association is working with a group of professional appraisers on new legislation. Developing legal parameters that will “address the concern that authenticators have in continuing to provide their opinion on works’ authorship,” this newly formed alliance seeks to provide “a higher threshold and burden of proof for presenting authentication-based claims.” Evidently, this “Year of the Fake” has pushed both the legal and art worlds further together against a common enemy.[7]

As of August 2013, Freedman (of Knoedler) has had her lawyers argue that she was simply the victim to the schemes of New York art dealer Glafira Rosales, who herself is now faced with charges of tax evasion and money laundering connected with arranging sales of works forged by an unnamed Queens artist. Rosales supposedly accomplished the successful forgeries by having her boyfriend put the canvases through exposure to the heat, cold, and the elements in order to achieve an aged look.[8] Considering this one point further, it is difficult to dismiss the interesting thought that a worn canvas wanting conservation would warrant its authenticity. Imagine if these works had been considered by a conservator after sale, as authentic items needing treatment? Would the purportedly infallible science of art conservation be able to uncover the lies? Or would they simply cover it over even more?

Freedman is also facing accusations of failure to do due diligence when she encountered the works, which she denies based on the involvement of twenty other “experts” she consulted.[9] The Knoedler scandal as of 2013 has opened up a great deal of discussion regarding art attributions and, in so doing, has drudged up the figure of the untrustworthy art dealer. After all, art is a business, is it not? It all comes down to a question of whose responsibility it was to examine the art works’ authenticity. If none claims full responsibility, then who in the world of art dealing can be trusted? While it is a business, this past year has certainly made clear the inherent issues of greed and deception that infiltrate the art world as much as they do Wall Street.

ICE with seized Items from Kapoor. Photo: Chasing Aphrodite.

December brought to light more actions of questionable legality in the figure of antiquities dealer Subhash Kapoor and a Belgian collector working with Sotheby’s auction house. Chasing Aphrodite has examined the unraveling of Kapoor’s decades-long webs of trickery in the sale of stolen ancient artifacts. According to those who have worked closely with Kapoor, he has been instrumental in laundering looted goods, formulating false ownership histories, hiding stolen art.[10]

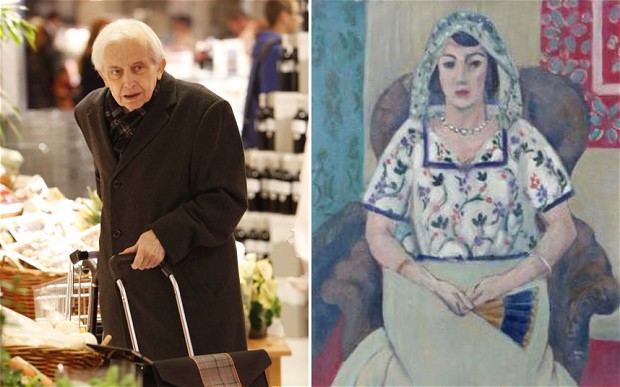

On the subject of looted artworks, from Germany came more news on the 2012 discovery of over 1,400 artworks stashed at the Munich apartment of Cornelius Gurlitt. These included pieces by Chagall, Picasso, Renoir, Dix, and Beckmann that his father Hildebrand Gurlitt had acquired during the short-lived Third Reich. Meanwhile, it has also been suggested that there could be several fakes within the collection. Spiegel reported in November 2013 that just under 600 of these works were illegally confiscated from their Jewish owners by Nazis. Hildebrand Gurlitt was known to have had close connections with members of the Third Reich and was known by American military art inspectors as “an art dealer to the Führer.” Investigators further reported that he served more widely as “an art collector from Hamburg with connections within high-level Nazi circles. He acted on behalf of other Nazi officials and made many trips to France, from where he brought home art collections. There is reason to believe that these private art collections consist of looted art from other countries.”[11] The 2012 seizure of his collection by the German government, as a result of tax investigation, understandably created a spike in coverage about issues of Nazi-looted artworks. One might think this is strange, considering the fact the war ended nearly 70 years ago. However, recent news reports relate that Cornelius Gurlitt is suspected of slowly selling off pieces from his father’s collection over the years. While Gurlitt Jr. claims private property ownership on these now government-confiscated works, his using them as loose capital to pay personal bills would be quite the convenient way to dispose of them into unconnected hands.[12]

Gurlitt (left) and a Matisse in his collection (right) Photo: Vantagenews.co.uk.

Now, Bavarian lawmakers are looking to change a law concerning pieces of art acquired in bad faith. In late November of last year, Bloomberg reported that Winfried Bausback, the justice minister in Bavaria, presented a proposal to the Justice Department that a 30-year statute of limitations on an artwork should be revoked, if that work was fraudulently acquired or inherited. If previous owners could now demand restitution for looted works, this law change could, as Bausback mentions, “[bring] to light an issue that was not tackled and certainly not resolved after the war.” Now, it is up to the German government to show persistence in researching artworks’ provenance in order to ensure a just end to this story seven decades in the making.[13] According to the Antiques & Fine Art News, the German government has decided to post photo documentation of more than 400 of the allegedly stolen works in the interest of attracting rightful owners’ claims. Yet another news story reminds us that these 70 year-old injustices against cultural heritage are still lingering in our midst: just last week The New York Times reported on the upcoming sale of three paintings seized by the Nazi’s from important French collections.

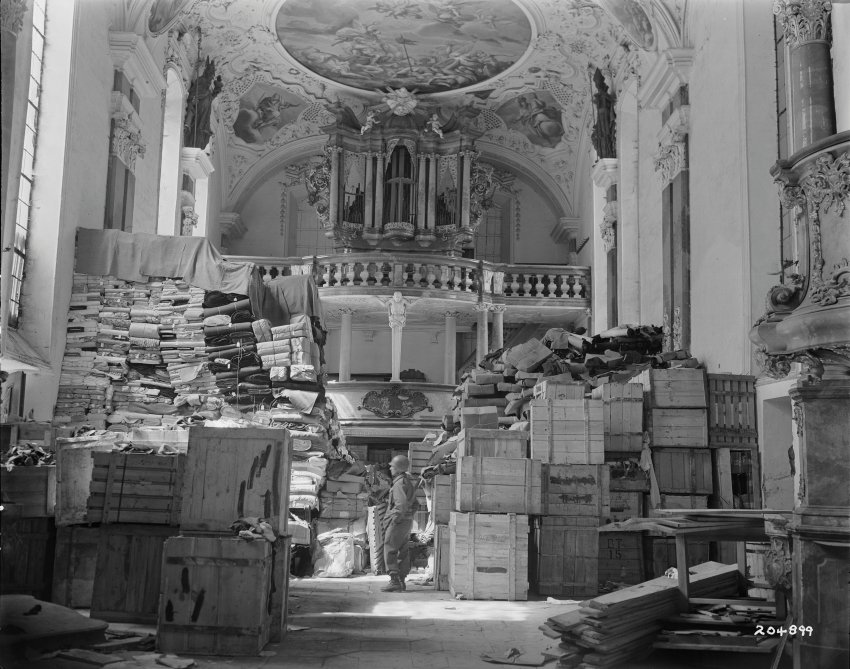

The upcoming movie Monuments Men (in theatres February 7) brings the issue of looted art restitution to the masses. Director George Clooney has taken on the story of Capt. Robert K. Posey and his band of art-rescuing brotherhood through a Hollywood lens chock-a-block with A-list actors. The film has also spurned a support effort from its producers for the rightful recovery of works of art and archival documents still missing. At the Monuments Men Foundation website, one can report tips and “join the hunt” for “most-wanted” items stolen by Nazi looters.

U.S. soldier viewing art stolen by the Nazi regime and stored in church at Ellingen, Germany. Photo: U.S. National Archives.

[1] Charlotte Burns, “Knoedler forgery scandal grows,” 9 January 2012. The Art Newspaper, News, Issue 231 (January 2012). http://www.theartnewspaper.com/articles/Knoedler-forgery-scandal-grows/25427 (last accessed 17 January 2014).

[2] Danielle Rahm, “Warhols, Pollocks, Fakes: Why Art Authenticators Are Running For The Hills,” 18 June 2013. Forbes. http://www.forbes.com/sites/daniellerahm/2013/06/18/warhols-pollocks-fakes-why-art-authenticators-are-running-for-the-hills/ (last accessed 24 January 2014).

[3] Scen Röbel and Michael Sontheimer, “The $7 Million Fake: Forgery Scandal Embarrasses International Art Wolrd,” 13 June 2011. Spiegel Online. http://www.spiegel.de/international/zeitgeist/the-7-million-fake-forgery-scandal-embarrasses-international-art-world-a-768195.html (last accessed 26 January 2014).

[4] Julia Michalska, Charlotte Burns, and Ermanno Rivetti, “True scale of alleged German forgeries revealed: Major auction houses and galleries have been caught up in Beltracchi’s fake art scam,” 5 December 2011. The Art Newspaper. http://www.theartnewspaper.com/articles/True-scale-of-alleged-German-forgeries-revealed/25235 (last accessed 26 January 2014).

[5] Burns.

[6] Irina Tarsis, Esq., “Will the Real Andy Warhol Please Stand Up: the Authentication Board to shut down,” 24 October 2011. Center for Art Law. http://itsartlaw.com/2011/10/24/will-the-real-andy-warhol-please-stand-up-the-authentication-board-to-shut-down/ (last accessed 31 January 2014).

[7] Hanoch Sheps, “A Plethora of Fakes and a Series of Thoughts: Where Has All The Real ‘Art’ Gone?” 24 December 2013. Center for Art Law. http://itsartlaw.com/2013/12/24/a-plethora-of-fakes-and-a-series-of-thoughts-where-has-all-the-real-art-gone/ (last accessed 26 January 2014).

[8] Laura Gilbert, “Art dealer is believed to be co-operating with federal authorities in fakes case,” 16 August 2013. The Art Newspaper. http://www.theartnewspaper.com/articles/Art-dealer-is-believed-to-be-cooperating-with-federal-authorities-in-fakes-case/30209 (last accessed 17 January 2014).

[9] Laura Gilbert, “Knoedler gallery fakes case heats up,” 11 September 2013. The Art Newspaper. http://www.theartnewspaper.com/articles/Knoedler-gallery-fakes-case-heats-up/30423 (last accessed 17 January 2014).

[10] “Kapoor,” Chasing Aphrodite. http://chasingaphrodite.com/?s=kapoor (last accessed 26 January 2014).

[11] Druckerversion, “Art Dealer to the Führer: Hildebrand Gurlitt’s Deep Nazi Ties,” Spiegel Online. News. International. http://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/hildebrand-gurlitt-and-his-dubious-dealings-with-nazi-looted-art-a-940625.html (last accessed 16 January 2014).

[12] Bruno Waterfield, “ ‘They have to come back to me,’ Cornelius Gurlitt demands Nazi-era hoard back,” 17 November 2013. The Telegraph. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/germany/10455300/They-have-to-come-back-to-me-Cornelius-Gurlitt-demands-Nazi-era-art-hoard-back.html (last accessed 16 January 2014).

[13] Alex Webb, “Bavaria Investigates Law Change to Reclaim Nazi-Seized Artworks,” 27 November 2013, Bloomberg, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/print/2013-11-27/bavaria-investigates-law-change-to-reclaim-nazi-seized-artworks.html (last accessed 15 January 2014).

However, in recent years there has been a tremendous amount of damage done to art objects that are even more difficult to protect, either from thieves, mentally-ill vandals, or just rowdy individuals. Public monuments, both architectural and sculptural, that are outside of the considerably safer museum environment, are more difficult to safeguard, even with the increasing presence of security cameras. Italy’s fountains are seemingly impossible to protect. In 1997, the Neptune fountain by Ammannati was vandalized twice, with the second incident resulting in the breaking off of one of the horses’ hooves. The city had recently installed eight remote control television cameras, though their view was obstructed by scaffolding. That same year, Bernini’s Four Rivers Fountain in Rome’s Piazza Navona was damaged when three men climbed onto the statue and broke the tail of a sea-serpent. (One of the perpetrators vowed to sue the city over damage to his foot incurred during the incident).

However, in recent years there has been a tremendous amount of damage done to art objects that are even more difficult to protect, either from thieves, mentally-ill vandals, or just rowdy individuals. Public monuments, both architectural and sculptural, that are outside of the considerably safer museum environment, are more difficult to safeguard, even with the increasing presence of security cameras. Italy’s fountains are seemingly impossible to protect. In 1997, the Neptune fountain by Ammannati was vandalized twice, with the second incident resulting in the breaking off of one of the horses’ hooves. The city had recently installed eight remote control television cameras, though their view was obstructed by scaffolding. That same year, Bernini’s Four Rivers Fountain in Rome’s Piazza Navona was damaged when three men climbed onto the statue and broke the tail of a sea-serpent. (One of the perpetrators vowed to sue the city over damage to his foot incurred during the incident).