Overwhelming Support as Landmarks Works Through the Backlog of Proposed Sites.

Ruth Osborne

Last Thursday morning at the Municipal Building at No. 1 Centre Street. dozens more supporters of landmark designations in New York City demonstrated their care for historic preservation in the city as well as their respect for the Landmarks Preservation Commission’s noble mission.

GVSHP representative speaking at LPC hearing, Nov. 5, 2015.

This was another in a series of public hearings and viewings begun this July as part of the LPC’s “Backlog Initiative”. Reports on last month’s hearings have demonstrated just how greatly communities back the Commission’s initiative to designate and protect historically significant properties and neighborhoods.

33-43 Gold Street. Courtesy: MakeSpace.

The buildings up for consideration this time around included:

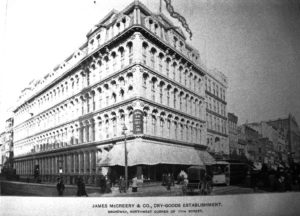

* no. 801-807 Broadway, one of the few remaining 19th century cast-iron facades in the city and one that has played a significant role in the historic commercial development of the area and survived destruction by fire over 40 years ago

* no. 33-43 Gold Street, an 1840s Romanesque Revival style building now known as the Excelsior Power Company Building

* no. 2 Oliver Street, an 1820s Federal rowhouse

* no. 57 Sullivan Street, an 1810s Federal wood-framed rowhouse

* no. 850 12th Avenue, the McKim, Mead & White Beaux-Arts IRT powerhouse, now used by ConEd

ames McCreery & Co. Building at 801-807 Broadway in 1895. Courtesy: Tom Miller.

The above-mentioned structures were the ones that seemed to receive the most attention from speakers. The arguments made for the designation of these buildings were very prudent and practical, despite what many detractors may say about extremists that want to freeze the city in time. Those who gave their testimonies in favor of designation (which was everyone who spoke over the course of the hour and a half that we observed) stated that current residents have not been inhibited by Commission oversight, therefore making landmark status not detrimental to their future well-being. Then why not grant designation after all?

IRT Powerhouse by McKim, Mead & White. Courtesy: NYC.GOV.

While the overwhelming support for protection of these sites as landmarks was obvious to everyone in the room, it was also painfully obvious just how little consideration the Commission is given as a city agency. The room itself was bursting at the seams with residents seeking to state their positions before the commissioners. There were just over 50 seats for press, participants, and observers. The rest were forced to overflow outside to the adjacent room, standing alongside walls, in doorways, and in an extra corner they could find. Is there any wonder why an argument has been made to provide the Commission with more resources to accomplish its mission?

Those represented before the Commission were a smattering of long-term neighborhood residents, students, tour guides, preservationists, architects, and politicians: the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation (a mighty advocate in recent years), the Victorian Society of New York, BIG architecture, the Society for the Architecture of the City, the Hudson River Powerhouse Group, Councilman Corey Johnson, and Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer. Nearly all of these speakers went over their allotted three minutes, demonstrating their strong sense of duty in declaring the significance of these sites as city landmarks.

57 Sullivan Street. Courtesy: Tom Miller.

According to one speaker’s experience, travelers coming into the city express shock that such significant structures have gone unprotected for so long. Not only was the argument made to preserve buildings as emblems of important design and architectural periods in New York, but also as markers of significant technological, commercial, and immigrant population change that formed the backbone of the city’s character and impacted the rest of the nation throughout history. Supporters of preservation do not care solely for structures as lavishly ornamented monuments to wealthy families past – they care deeply for their city’s rich history, something they find personal connection with in some form or another. The preservation of these buildings in question, as was made evident by the speakers’ testimonies, would serve to validate the value of the immigrants, artists, architects, merchants, and transit workers who worked and made their home in New York in centuries past. Historic structures offer diversity in the architectural landscape of the city – not uniformity. And, as borough president Brewer pointed out, the place of public discourse on New York’s ever-development landscape is an essential element in good stewardship of this city that millions call home. We at ArtWatch greatly appreciate the time and energy the Commission has provided for these public hearings and their thoughtful consideration as they work through proposed designations.

On the other side of the Atlantic, the topic of heritage preservation is being revisited with the re-launch of historian David Lowenthal’s renowned book The Past is a Foreign Country (1985). The Warburg Institute will host an event on November 11th to commemorate Lowenthal’s significant effort in investigating the 20th century culture of conserving heritage. His work has been a cornerstone for contemporary study of how the past is preserved, re-enacted, remembered, and celebrated. Additionally, the upcoming ArtWatch UK Journal will feature an article by art historian Florence Hallett on issues of heritage preservation in England. What British preservationists are finding is that their architectural heritage is being mixed up with competing social policy trends. When the motives behind spending and support for historic preservation get caught up in policy and legislation, on both sides of the Atlantic, these complications interfere with the care available for the buildings themselves in the future; in the end, resulting in damage that cannot be recovered from easily (if at all in some cases).

Finally, later today, ArtWatch will join others again at an LPC hearing to provide support for the continued preservation of the Gansevoort Market Historic District in downtown Manhattan. The GVHSP has sustained a brilliant campaign against the proposed overdevelopment plan for the historic market buildings on Gansevoort. According to their website: “If approved, the development would not only destroy Gansevoort street and the surrounding historic district’s unique sense of place, but set a terrible precedent regarding the type of construction allowed in landmarked districts.” Stay tuned for reports!