Review: Center for Art Law Event “F for Fake”

Ruth Osborne

Orson Welles in “F for Fake” (1973)

Last week, the Center for Art Law hosted an event at the Brooklyn Law School regarding the (unfortunately) highly relevant topic of fakes and forgeries on the art market.

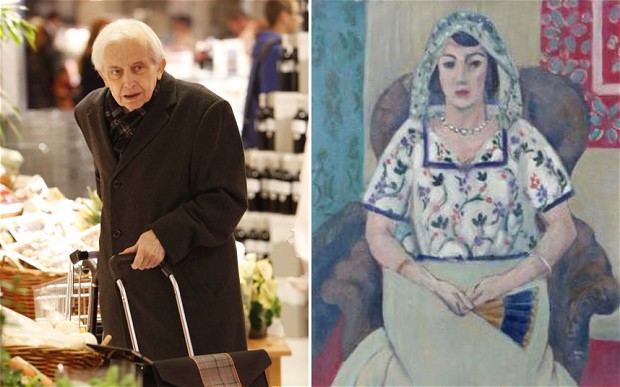

Irina Tarsis, Esq., Founder and Director of the organization, introduced Orson Welles’s 1973 film “F for Fake” to begin a discussion on the various parties involved with forged artworks and their respective motivations.

A presentation followed by Aaron H. Crowell, Esq., a partner at Clarick, Gueron, Reisbaum LLP who was a member of Eleanore and Domenico De Sole’s litigation team during the massive Knoedler trial in 2015-2016. Crowell brought up the issue of which side gets the most blame in these cases, and in Welles’s film: the art experts. The art experts are the ones who appear (misleadingly, and sometimes unbeknownst to them) as verifiers of a forgery. The art experts are the ones who can insist a work is authentic, only for a scientific test to prove it’s a forgery. But, as Crowell insisted, the focus on the experts as villains misses a more prevalent issue enabling the steady stream of fakes onto the art market.

Rather, the art world and the public at large act willingly as voyeurs looking for another “newly discovered” work, seeking the thrill of viewing a work by one of the old masters. That the art world at large still holds onto the Renaissance myth of the artistic genius is very true. But is it something that we can truly move away from? Would the public value of artworks risk being diminished if we did move away from this myth?

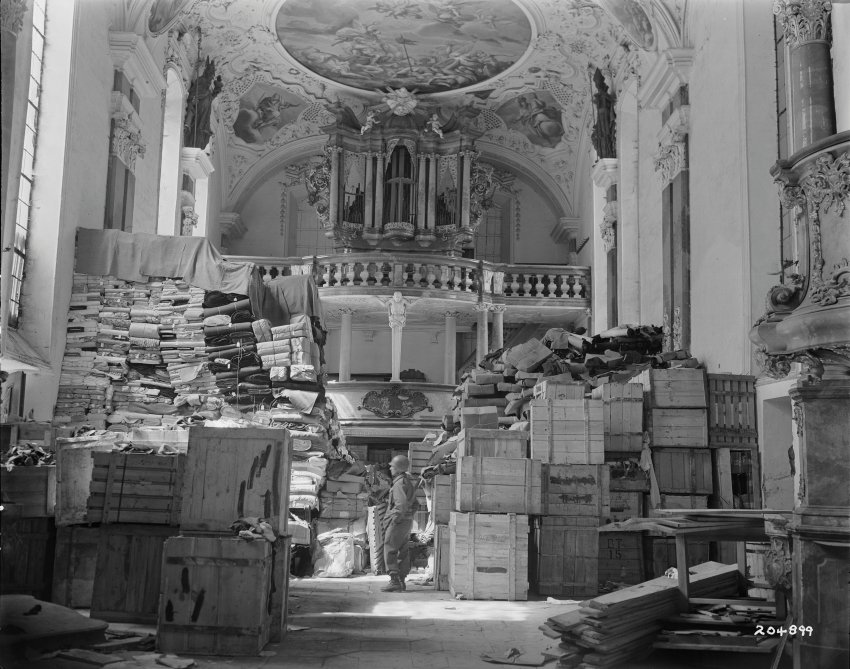

The de Soles at Trial in 2016. Courtesy: ArtNet/Elizabeth Williams/Illustrated Courtroom.

This discussion should serve as a reminder to approach connoisseurship – not avoid it entirely – in a manner that seeks as objective a point of view as a flawed human can have. In doing this, we might be more aware of potential shortcomings in our ability to truly see a work of art for what it is, to critique its value, aesthetically and monetarily. Another essential matter to consider that always lies in the background of art market forgeries is that it is in fact a commercial market, in the sense that a market and its players can act wildly in order to drive up demand for a work to drive up a value. These market forces themselves have a rather deep impact on the prevalence of fakes, on what is authenticated and why, and on the ultimate valuation of an artist and his or her real or imagined oeuvre (see here for Scott Reyburn’s review of “insider” books on the art market today).

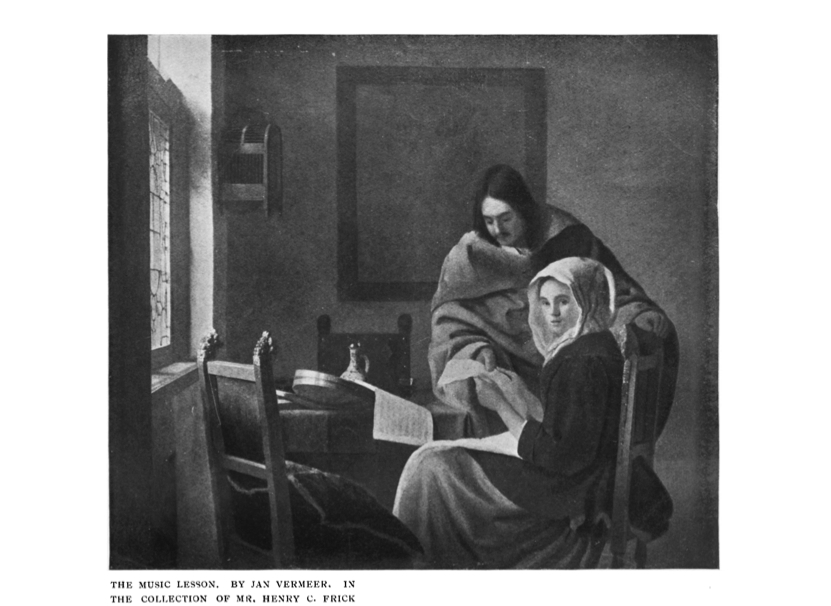

Painting sold by Knoedler as a Rothko to the de Soles. Courtesy: ArtNet.

The “crisis of connoisseurship” that we are seeing in today’s art market and museum world has been thoroughly addressed already at the December 2015 conference “Art, Law and Crises of Connoisseurship” (put on by ArtWatch UK, the London School of Economics, and the Center for Art Law). We encourage our readers to take a look at the topics each speaker addressed, and to be on the look out for the upcoming publication of papers from this conference.

By Ruth Osborne