The Menil’s Picasso: A Victim of Vandalism or Adaptive Reuse?

Einav Zamir

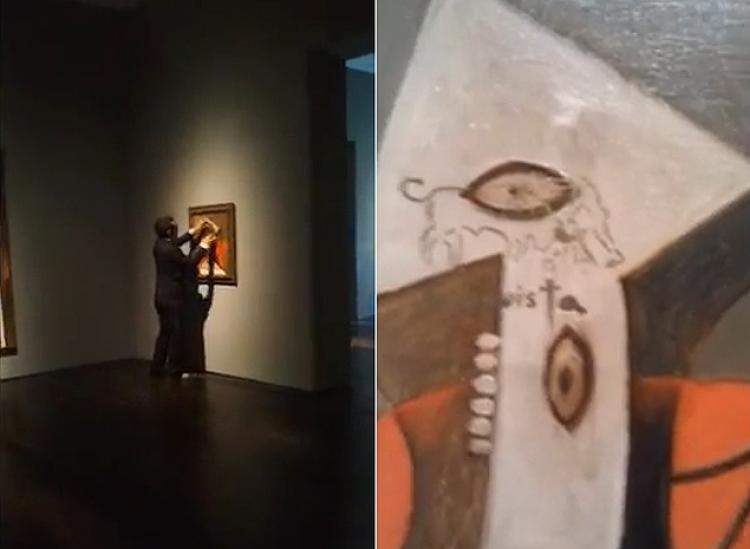

Left: Uriel Landeros vandalizing a Picasso painting, Right: Picasso’s work after Landeros’s alterations.

The recent “tagging” of Picasso’s Woman in a Red Armchair in Houston raises questions of ownership, as parties weigh in on the implications of vandalism.

This past June, 22-year old Uriel Landeros entered the Menil Collection with a can of spray paint and a stencil. As seen in a video taken by a witness, Landeros quickly defaces the painting, rips the stencil roughly from the surface, and exits through a side door. He is currently in hiding, and faces several felony charges that could result in up to 10 years of prison and a $10,000 fine.

Perhaps riding on the public outcry against the young Houston artist in recent months, the Cueto James Art Gallery chose to stage a show of a dozen original Landeros pieces – essentially treating the act of vandalism as a work of art in itself by rewarding the perpetrator. The sardonically titled exhibition, “Houston, We Have a Problem,” opened in late October to much fanfare and spectacle. It seems somewhat akin to Tate Modern’s proposed exhibition, “Art Under Attack,” set to begin in October of next year. This show will examine recent acts of vandalism – such as that carried out on Mark Rothko’s painting, Black on Maroon – as something of cultural curiosity rather than criminal behavior. Both shows have gained a fair amount of media coverage thus far, however James Perez, owner of the Cueto James Art Gallery, has denied that the showcase is meant to stir up publicity, stating “I’m already popular. This is for Uriel.”

Still, one wonders whether the attack on the Picasso was aimed at gaining attention for the artist’s cause, rather than for creating something of artistic value, as was certainly the case for Polish artist Vladimir Umanets, who vandalized the aforementioned Rothko painting in support of “Yellowism.” Further, Perez believes that the process of tagging another’s work is like “taking something and making it your own,” which begs the age-old question of who, if anyone, can actually own a work of art. Should an individual have the right to tamper with something that belongs to society as a whole? This question is complicated further by the fact that the painting itself is considered private, rather than public, property, forming the very basis for the charges held against him. Cultural value does not come into play, in this regard.

In either case, restoration efforts are expected to result in a “full recovery,” though the overall lack of concern for the painting and for the Menil Collection on the part of both Landeros and Perez is disconcerting, to say the least. In a video posted by Landeros on YouTube this past August, he claims that he never intended to “destroy Pablo’s painting or to insult the Menil,” yet goes on to say that the spray paint could simply be removed with “a little bit of Windex.” Likely, the restoration will be more complicated than that, and as Uriel Landeros continues to receive attention from the public, Picasso’s Woman in a Red Armchair slowly returns to its former state. If such acts of vandalism occur in the future, as they certainly will, the question remains whether it is fair to hold our artistic heritage hostage for the sake of individual beliefs.

However, in recent years there has been a tremendous amount of damage done to art objects that are even more difficult to protect, either from thieves, mentally-ill vandals, or just rowdy individuals. Public monuments, both architectural and sculptural, that are outside of the considerably safer museum environment, are more difficult to safeguard, even with the increasing presence of security cameras. Italy’s fountains are seemingly impossible to protect. In 1997, the Neptune fountain by Ammannati was vandalized twice, with the second incident resulting in the breaking off of one of the horses’ hooves. The city had recently installed eight remote control television cameras, though their view was obstructed by scaffolding. That same year, Bernini’s Four Rivers Fountain in Rome’s Piazza Navona was damaged when three men climbed onto the statue and broke the tail of a sea-serpent. (One of the perpetrators vowed to sue the city over damage to his foot incurred during the incident).

However, in recent years there has been a tremendous amount of damage done to art objects that are even more difficult to protect, either from thieves, mentally-ill vandals, or just rowdy individuals. Public monuments, both architectural and sculptural, that are outside of the considerably safer museum environment, are more difficult to safeguard, even with the increasing presence of security cameras. Italy’s fountains are seemingly impossible to protect. In 1997, the Neptune fountain by Ammannati was vandalized twice, with the second incident resulting in the breaking off of one of the horses’ hooves. The city had recently installed eight remote control television cameras, though their view was obstructed by scaffolding. That same year, Bernini’s Four Rivers Fountain in Rome’s Piazza Navona was damaged when three men climbed onto the statue and broke the tail of a sea-serpent. (One of the perpetrators vowed to sue the city over damage to his foot incurred during the incident).