Art Law Focus on : Art Forgery

Angelea Selleck

Christie’s New York. Courtesy: Christie’s.

Art forgery has existed for centuries. However, in recent years it seems more prevalent in the art world and its presence is unsettling. In such a litigious society as that of the USA, it is crucial that experts, dealers, auctioneers, curators and gallery owners all play by the rules when purchasing a new work of art.

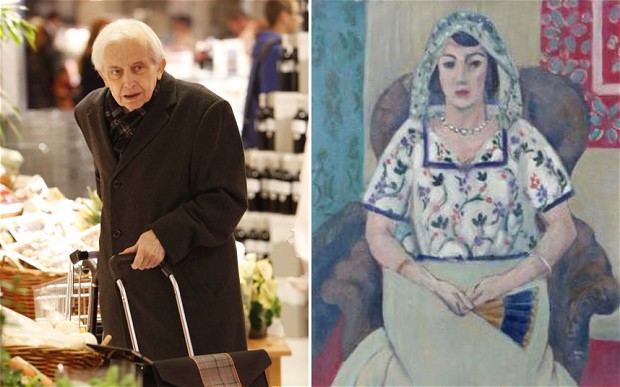

It is integral that a work has proper provenance documentation, that there has been an application of connoisseurship to the work’s visual and physical aspects and in some cases, scientifically tested to determine the works physical properties. In other words, the piece should be authentic and be submitted to the authentication process in order for it to be offered for sale. Nonetheless, art forgery persists and despite the art market’s best efforts, fakes are being sold for millions of dollars around the world. In 2013, Christies and Sotheby’s earned over an estimated $3 billion in auction sales combined.[1] Even if the proportion of forged or misattributed works are small, the number of cases could be large.

While some high-profile cases of forgery have gone to trial and a culprit has been determined, it is important to recognize that there is never one person responsible for a forged work on the market. There is a long assembly line that brings the faux work from the forger’s hands to an auction house or gallery. In addition, the number of cases that have come to light makes one question the ethics by which the industry operates. In many forgery cases, the ones accused of fraud or negligence by selling the works under false labels are quick to protest their innocence but, nota bene, these are the professionals in charge of our artistic heritage. These are the persons who have, wittingly or unwittingly passed on false goods when their professional standing depends on the soundness of their judgements and the reliability of their claims.

Art Forgery: the Issues

While the trade’s ethics may seem questionable it is important to point out that detecting a forged work can be very difficult. Pinpointing a culprit is very difficult in forgery cases; it all depends what the facts are, what the art is, how many works are involved and how expensive they are.[2] Today, fakes can pass off as genuine and even get a stamp of approval by art experts. In addition, there is also reluctance from art experts to speak out if they suspect a fake. In fact, institutions such as the Andy Warhol Foundation and Lichtenstein Foundation have stopped authenticating artwork and pointing out suspected fakes for fear of lawsuits from the owners of works they reject.[3] Because art has become such a lucrative business and the prices of pieces are exponentially rising there is much more at stake for experts to give their opinions on pieces. At the end of the day, the work has to sell and some who harbor doubts or suspicions choose to keep mum in order to protect their jobs. On the other hand, turning a blind eye to a fake is irresponsible and detrimental to the art market. If confidence in the art market is to be maintained, all works of art must be thoroughly examined and rigorously appraised before being authenticated. Dealers and auctioneers serve to a considerable degree as stewards of our artistic heritage. If they do not live up to their professionally claimed competence and probity the consequences for confidence in the wider art market could prove dire.

Sotheby’s Helena Newman, Philip Hook, Melanie Clore. Courtesy: Sotheby’s.

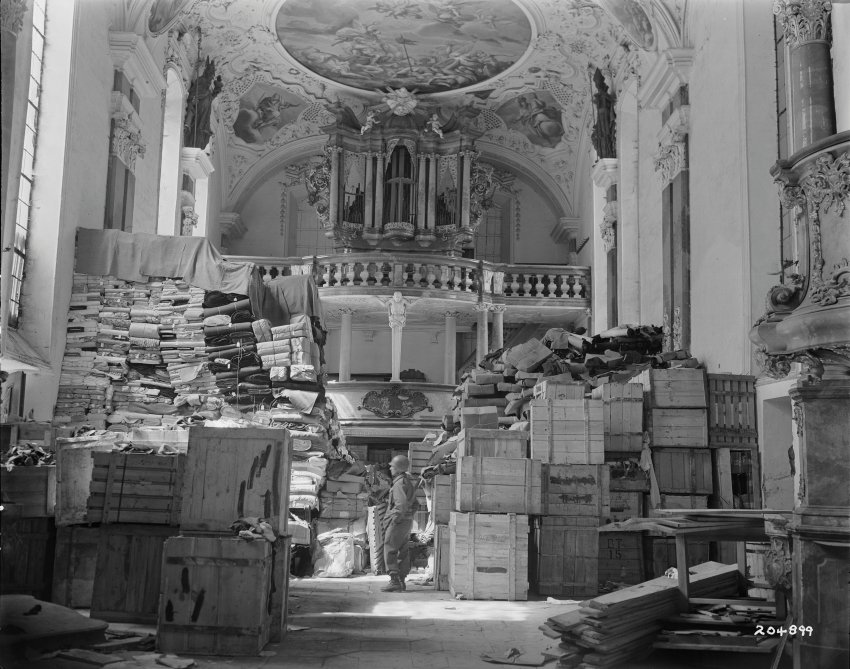

As things stand, it is very difficult to regulate the art trade and there is little legal power over the market. In the United States, there is no legislation that deters forged art works from entering the market. There are other modes that create standards for professionals such as the Art Dealers Association of America (ADAA) and the Association of Museum Directors (AAMD). Both bodies demand professionals practice due diligence in verifying the accuracy of information supplied to a buyer.They are not required to guarantee the accuracy of certain information such as the date of a work, its provenance, or exhibition history. Thus, it would seem evident that there is an overall lack of liability and accountability in the workings of gallery owners.

Even when fakes have been exposed it is difficult to prevent them from re-entering the market. In Europe, where there are stricter rights for the arts, droit morale, fakes can be destroyed as directed by the artists or relative of a deceased artist. This in turn combats fakes from being re-circulated back onto the market and the possibility of it ending up in a gallery that believes it genuine. Nothing of this sort exists in the United States. Some have suggested that when a fake is determined the piece should be stamped in order to deter it from being sold as genuine years later. This has yet to be implemented or practiced.

So what does this mean?

Marion True inside Getty warehouse, 1988. Courtesy: The Art Newspaper.

All things considered, art is a business. The art market is a principal medium through which the artist’s work is distributed and bought by art consumers. Furthermore, art works are treated as articles of commerce or commodities. And it is perhaps due to this business-minded perspective that the codes of ethics and standards held to museum professionals are not met when they are presented with a work of art with questionable provenance. However, recent court cases have taught dealers, curators, auction houses, museums and gallery owners to pay exceptional attention to what they are buying and from whom (i.e., the cases of Marion True at the Getty Museum and the demise of Knoedler & Company). The point made here is that, while art forgeries can be difficult to detect and regulate, it is still of utmost importance that galleries, museums and auction houses uphold a code of ethics. They need to properly authenticate the work they are buying and demand all documentation. After all, it is their responsibility and duty as guardians of our artistic heritage. While there are some initiatives and agreements that museums and galleries abide by, such as the AAMD and ICOM, there still seems to be a lack of accountability. It seems in many cases that the money and prestige involved in acquiring a work of art can cloud the judgement of those involved in dubious acquisition.

In sum, art forgers and dealers of questionable morality will always be present in the art world. But what can change is how private buyers as well as museums and galleries acquire works of art. There is great necessity to enforce higher standards if they do not want to be victims of scandal. And until this is done, cases of art forgery will persist.

[1] “A Record-Breaking Year at Auction: A Look Back at 2013,” MutualArt. 2 January 2014. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/mutualart/a-recordbreaking-year-at-_b_4530126.html (last accessed 13 May 2014).

[2] Cohen, Patricia, “Fake Art May Keep Popping Up for Sale,” New York Times. 5 November 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/06/arts/design/murky-laws-give-fake-artworks-a-future-as-real-ones.html?_r=0 (last accessed 14 May 2014).

[3] Kinsella, Eileen, “A Matter of Opinion,” ARTnews. 28 February 2012.http://www.artnews.com/2012/02/28/a-matter-of-opinion/ (last accessed 14 May 2014).