Readability of a Painting: Visibilité en peinture, lisibilité en restauration – L’objectif de lisibilité en restauration et ses conséquences sur les peintures

The pictorial work is recognized as such and preserved in museums by virtue of its singular identity. The exceptional man who fashioned it makes visible, through its plastic organization, a plurality of messages. Wanting to make visible the visible is to impose a limiting reading of a work that has been designed to transmit, by the sensitive, an infinity of meaning. Readability is a fuzzy, undefined concept that constitutes an inadequate framework for restoration and can have destructive consequences on paintings.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

According to the director of C2RMF, Jean-Pierre Mohen, ” readability, that is to say, the understanding that the public has of the work, remains our main objective ” [1]. What does one want to make “readable” when restoring a work that is apprehended by the “visible”? The question is not just about optical comfort, but touches on the fundamental problem of the nature and status of the work of art. Indeed, current restorations, practiced in the name of readability, profoundly transform the works. To understand why, we first examine what makes the specificity of the work of art, before asking if the principle of readability in restoration is appropriate to address the pictorial work.

The nature of the artwork

One of the characteristics of a work of art is to be shaped by an artist, a man who has an aesthetic intention and who plans to submit his creation to the aesthetic appreciation of the viewer. Thus, the painter uses the means of expression which are his own – the forms, the colors, the drawing, the lights – and tries to find the plastic organization which will give the most aesthetic potentialities to his work. But there are also objects that have been shaped by men with other intentions (religious, religious …). These men were not artists (often this category did not exist), but people specially chosen for their abilities to work and to transform a material in order to endow it with a certain force of presence. Yet, if we have gathered in art museums an Egyptian sculpture, an African mask, a Titian painting and a paper-glued Picasso, it is that we have considered that these objects – beyond their identities and functions first, beyond their history – are works of art, that is to say, masterful artistic achievements capable, in themselves, to create an aesthetic fascination for the viewer.

The works of art condense material, formal and stylistic wealth in a unique and indivisible totality, in which their aesthetic, symbolic and historical dimensions are revealed. Because they were created by a man of exceptional character, they express these different dimensions in an original and inimitable style. In this sense, works of art are not objects , which can be repaired or reconstructed, from which one can separate the elements. They possess a singular identity, irreducible to any manipulation and appropriation. Our society gives these works a very specific value as the highest and most absolute testimonies of our humanity. So that the way we look at these masterpieces defines an ethical relationship and places us in a moral duty towards them.

Visibility in painting

How does the painter work a material to make visible what he wishes to convey to the viewer? The “plastic” work of the painter consists mainly in ordering the surfaces of his canvas and prioritizing them in different planes. He defines what he wants us to see by making more or less apparent, more or less present, parts of his painting. This ordering of the visible is essential because it gives the painting its space and its scale, as well as its coherence and its plastic unity.

To do this, the painter has an infinity of shapes, shades of color, and light effects that he must orchestrate. Thus, by the use of warm or cold colors, the painter distributes plans that are deep. By nuancing and spreading splashes of color and light in the space of his canvas, he organizes visual circulation and strives to create a chromatic harmony that will give the canvas its colorful unity. It will create sensations of space, scale and chromatic harmony that are very specific to painting, not realistic or descriptive, but that can be found in an Egyptian fresco, a Japanese print, a work of art. Vinci, Kandinsky or Basquiat.

For example, the sensation of pictorial space is engendered by the way the planes of the painting are arranged, which arranges the eye movement and gives the work its full scale. Think of Raphael’s Three Graces (Condé Museum) or Vermeer’s Lacemaker (Louvre Museum), which are small works but have an expressive dimension that largely transcends their real dimensions. In the same way, by the use of colors, the painter leads his work to a point of chromatic equilibrium which can as well emerge from violent contrasts (this is the case of Picasso’s canvases which are balanced by the play of very dissonant colors), as very slight modulations of a restricted color range (as for example at Morandi). To reach this final colored unit, the painter often uses glazes which are the last very thin and very fragile layers which allow him to dose his colors, to attenuate or accentuate such brilliance, in order to establish the overall harmonization of his canvas.

Thus, to give his space, his scale, his light and his rhythm to the painting, to give to see his work, the painter distributes the forms, the colors, the luminosities, as a playwright distributes roles: he arranges the characters, the objects, the decoration, or the surfaces in their relative places according to the importance and the meaning which it wishes to give them. He establishes degrees of visibility between the different parts of his painting and defines what will be the general visibility of his painting. By carrying out this ordering of the pictorial material, it offers a plastic organization to our sensitive perception, it makes visible a subject, a symbolic, an aesthetic. It is in this work of the visible that his creative abilities are manifested and that the human message he transmits is embodied.

Readability in restoration

The painter finished his painting when he considers that he has carried the pictorial material that he works to a state of general visibility that satisfies him. But over time, this matter is changing: the colors change, varnishes are spinning; there may also be accidents or deliberate alterations (vandalism or alterations). These changes in material, hues and tones necessarily affect the initial state of the painting. It was then that the Conservatives ordered to restore with the desire to make the work more readable . This is the case for example when one considers that the aging of the varnish alters too much the colors of a painting and that it is necessary to proceed to its devernissage / revernissage. Or when we consider that repaints or accidental alterations obstruct the readability of the work.

But the notion of readability raises many questions: What readability are we looking for? How can we make the work more readable, that is to say, more intelligible and more understandable? Why do you want to make the visible visible? Why do you want to give something to read that, by nature, is apprehended by the sensible? In fact, the objective of readability in restoration faces a fundamental problem: we know that there has been a change in the material, but we can neither measure the changes, nor know with certainty the original state paint.

Indeed, the development of a work of art is a complex process, both scholarly and intuitive, that it is impossible to reconstitute scientifically. There are no documents or testimonies that could be considered as evidence for a reconstitution of the work, and scientific analyzes (pigment samples, paint layer analyzes, etc.) do not allow a reliable and exhaustive measurement of the modifications. of materials. In addition, the pictorial work is a material composed of inextricably mixed elements, so that in practice, it is very difficult to make alterations on materials that overlap and interpenetrate, without risking upset the balance pictorial of the work. Moreover, even if it were possible to know the initial state of a painting, the restoration would still encounter the irreducibility of the creative act. The multiple touches of a painting are posed by the artist’s emotion in a style that, because it is natural to him, remains inimitable. What is invaluable is the appearance of a new figure in the pulsation of a movement in Michelangelo, in the pulsating colors of Veronese. No one can adopt or mimic their temperament, no one can reproduce their style and their “genius”.

Faced with these difficulties, we understand that it is impossible to establish objective criteria that could tell us what today would be a “good” readability, and that seek readability, it is necessarily proceed to a reconstruction of the a work that will necessarily be different from that conceived by the artist. Here is the problem: the painter leads his work to a certain state of visibility. Time, as well as various alterations (including those produced by previous restorations), transform this work. The conservator, following the instructions of the curators, seeks a readability according to what he considers should be legible today. But how readable is it? What will be made more readable since it is absolutely impossible for us to know and reconstruct the initial state of the canvas? No clear and precise definition is proposed of this notion, which is increasingly used to justify all sorts of interventions. There are as many conceptions of readability as there are points of view. One can look for very different readings depending on whether one prefers historical, anthropological, symbolic or plastic readings. Lightening the varnish to make the colors more vivid, to make the details more apparent, it is to intervene on the pictorial organization in order to privilege a reading among others: the readability in this case would be to be able to read more details, more Easily, faster, thanks to less darkened colors.

Legibility is therefore based solely on the aesthetic criteria of the various stakeholders involved in the restoration process: art historians, curators, scientists, restorers. Aesthetic criteria that are, by definition, subjective, random and changing. This subjectivity is found at all stages of the restoration: (i) when judging whether a canvas is sufficiently legible or not; (ii) when deciding how to make it more readable; (iii) during the execution, in the same gesture of the restorer. In reality, wanting to make the work more readable is to reduce the work to a particular reading as it deploys, through its plastic organization, an elusive plurality of messages. The objective of readability thus diverges radically from this singular experience of the visible to which the painter invites the spectator before his work. Thus, after a restoration, the original intention of visibility of the painter has been replaced by the current intention of readability of the restorers (and their sponsors), who act according to more subjective motivations. or less conscious.

The results

What are the consequences of such restorations on works? The artistic value of a work is contained in a unique and indivisible totality, carried by its material, in a plastic balance (the ordering of the visible evoked above) so fragile that at all levels of restoration, it is very difficult to intervene without risking altering the unity of the work. It has also been shown how restorations aiming at readability, are based on an undefined concept, subjective, and likely to have very different meanings.

Despite the risks, despite such fragile foundations, for twenty years, thanks to new techniques, it is estimated to be able to intervene more radically. The restorations are not limited to a lightening of the varnish, but consist of deep interventions on the pictorial layer. Canvases, which are in good condition, are restored. In these cases, it is the objective of readability – with all that can be vague and subjective – which takes precedence over the conservation goal. This was the case for the Wedding of Cana Veronese, the View of Delft and the Girl with the Pearl of Vermeer, the Virgin with the Rabbit of Titian … Moreover one takes pretext of occasional alterations to carry out general aesthetic restorations, as was the case for Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel.

These restorations are very voluntary, and transform in a radical way – and irreversibly – the pictorial organization of the works: the effects of depth, scale, space, of colored unity, the organization of the plans, the circulation by passages or contrasts between these planes, the swinging of the forms between them, are upset. These plastic consequences, which are characteristic of restorations aimed at legibility, are found in a large number of paintings in the Louvre. We can make an inventory.

- Loss of color graduation between them . The colors, which previously were graduated between them in more or less intense tones, rub shoulders in equal intensities. Having become rivals, the colors cancel each other out and the painting loses its colorful unity (see The Holy Family of Bellini, the Virgin with Saint Catherine and Saint Rose of Perugino).

- Loss in the shades of each color . Each color, previously nuanced in different tones, is declined in a single shade (see The Marriage of Cana Veronese.The same red, the same blue, the same yellow, are used for all the characters, which gives the impression that Veronese used only one shade of color).

- Loss of the hierarchy of light effects . The luminous bursts are repeated identically, placing all the previously hierarchical elements in space, on the same plane, causing the general organization of the canvas to burst (see The Holy Family of Raphael).

- Loss of the passages between the forms . The different elements, previously interconnected by passing effects, are cut out in a uniform way. What causes a puzzle impression ( The Marriage of Cana Veronese, or The Holy Family of Bellini).

- Loss of the volume of forms . The transformations of values, colors and nuances, redefine shapes in different planes, flatten and distort them. The forms lose their volume and no longer define a coherent space (see The Holy Family of Titian).

- Loss of scale and space . Previously, the scale established by the ordering of the different planes, defined the space of the painting. The transformations of the luminous and colored hierarchy, the loss of the volumes, upset the ordering of the plans and disorganize the ratios of proportion between the various elements of the table. This provokes an effect of chaos, of piling up of forms (see The Abduction of the Sabines of Poussin, The Christ of Lotto, The Preaching of Saint Stephen of Carpaccio).

More generally, the transformations due to these restorations affect in the same way paintings by painters of very different times and styles. All that distinguishes the artistic genius in its capacity to create new spaces, original colorings, unexpected appearances, is standardized and one finds everywhere the same nuances, the same colors, the same sensation of flattening and heaviness . The works thus restored are artificially placed out of time and are all alike: their artistic riches are destroyed, their singular evocations are annihilated.

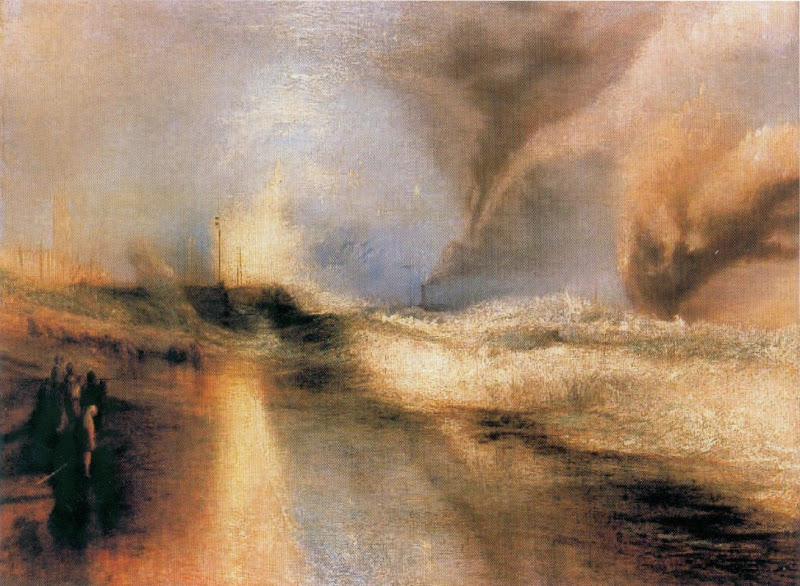

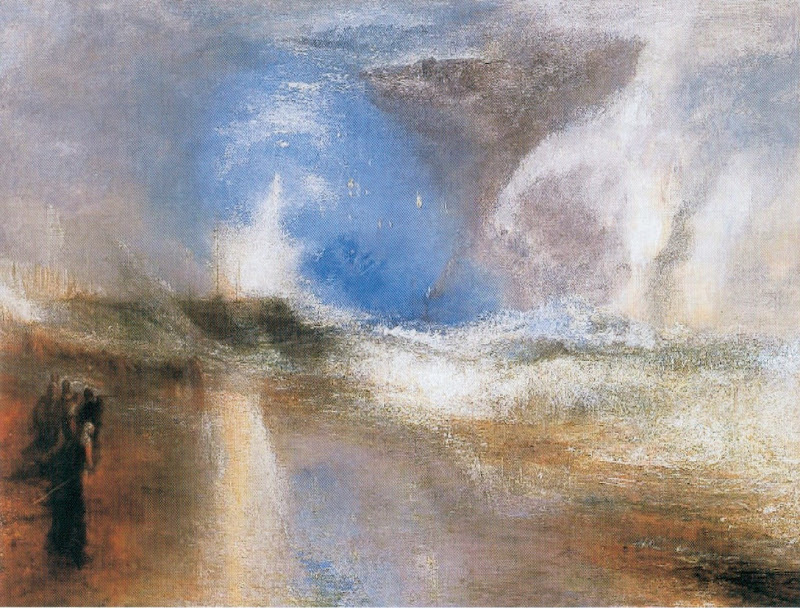

Restoration, which aims at readability, is therefore an aesthetic restoration that has important destructive effects. Let’s compare to the Louvre the Saint Jerome of Lotto (unrestored) to his Holy Family (restored).

The Saint Jerome is a small work, but the surfaces in shades of ocher, gray and green hot and cold, fit into successive plans, very skilfully paced, to define an immense space that gives this work all its scale. The painting is dark, in a limited range, but it remains very colorful. The muted colors are subtly modulated in an alternation of light and dark, so as to make Saint Jerome appear in its singular luminosity: the ocher-pink coloring of the character and the reddish coloration of the fabric bring a shade which, by contrast and by counterpoint, vibrate all the surrounding space. The fabric that envelops Saint Jerome models the character, he gives it body; it defines a volume that fits into a space.

The Holy Family is a larger work with another theme. Above all, it obeys a plastic layout of a different nature. The characters and landscape elements all stand out in the same way, with the same intensity, in equal values. The eye is everywhere solicited identically, the eye is dispersed and can no longer rely on the hierarchy of plans to circulate in the web. The colors are more vivid and stand out more (blue, yellow, white, green, red) but they remain local colors that do not define a colorful range. If there are many different colors, there is no more general color. The clothes of the characters are placed side by side, they are flat shapes that do not let guess the underlying presence of a body. Although the format is large, it does not feel great. On the contrary we have an impression of crowding, of clutter and painting has no scale. Major transformations in the plastic ordering of this painting have thus caused the general impoverishment of its artistic development.

Conclusion

Thus restored, what will be made more readable? As explained above, objective readability criteria can not be determined. One can always imagine being able to make more legible, or to make it readable otherwise. Current restorations show that, to varying degrees, the historical, iconographic and anthropological legacies are privileged, to the detriment of a preservation of the plastic order that contains the artistic value of the work. For the ” general public and schoolchildren ” [1], a literal understanding of the work is made, a certain readability is imposed, that is to say a subjective interpretation of the work. Didier Besnainou, art restorer, attached to the national museums and France, says it very clearly: the function of the restorer ” is comparable to that of the translator-interpreter.He like him, he is an adapter, aiming at the rebirth, the rediscovery, the recreation, taking care not to go as far as treason. “[2]

Note also that these plastic upheavals are irreversible. What has been removed can not be returned. And once disturbed, it is impossible to reconstruct the pictorial balance achieved by the painter. The choice of readability empties the works of their art and betrays their meaning.

It follows that the primary mission of protecting the artistic heritage is misguided. This moral duty that commits us to works and their creators is flouted. The inevitable subjectivity of restoration and the inherent fragility of works of art must lead us to reconsider the principle of readability – and, more generally, the objectives of the restoration, its limits and its modes of action. Faced with these many questions, it is possible to provide answers that take more account of the challenges of restoration, and to propose solutions that are more respectful of the specific identity of pictorial works.

For example, it is said that time degrades works and that it fully justifies that we restore them, that we try to make them more readable. Time is a natural process that has no consciousness, that has no intention, in this sense, its action is not subjective. Time causes changes in the material, but we can not evaluate them and above all, we can not remedy them. If the work does not remain intact, the human message left by the painter in his creative gesture is always present. The work keeps alive this human trace because even diminished, it remains authentic. Conversely, the restoration imposes an external intention on the work based on subjective criteria, and in doing so, it denies the inevitability of time and challenges painting in its very essence.

It is therefore important that restoration aimed at legibility be recognized as an entirely subjective process, which is based on aesthetic, changing and evolving choices (moreover, the restorers often denounce the aesthetic choices of their predecessors). Above all, it is urgent to measure the destructive effects. However, on the contrary, those who criticize these restorations are accused of subjectivity, we highlight the objectivity of science, and we brandish concepts that have all the appearance of common sense: “readability”, “return to the “origin”, “better understanding of the work”, “accessibility”, “democratization of art” … Seductive concepts but which are based on a priori subjective (therefore inappropriate to found a scientific approach) and which propose fuzzy criteria (accepted as self-evident) to define a totally inadequate framework for approaching the artwork.

However, it is possible to define the objectives and the practice of restoration differently: to favor preventive conservation, to accept the reality of time, and to choose to intervene on the works only in case of proven threats; not to carry out aesthetic restorations on works in a good state of conservation or requiring only occasional interventions; do facsimiles in the case of paintings too damaged to propose a version of what is supposed to have been the original work; make legible, iconographic messages legible … by means of appropriate reading materials: books and educational materials. There are therefore many alternatives, more respectful of this vital part of the work that we have the duty to transmit to future generations.

[1] Jean-Pierre Mohen, “More legible works and more accessible to the public”, Le Monde des Débats, September 2000, p. 31-32.

[2] Didier Besnainou, “Restoration, a singular art”, Beaux-Arts Magazine, December 2000.

L’esito finale di una iniziativa messa in opera più di una decina di anni fà, quando allora c’era il signor Rollandin, Presidente della Regione, René Faval, Assessore alla Cultura, il Dr. Domenico Prola e Flaminia Montanari alla Soprintendenza delle Belle Arti, si é concrettizzata oggi con questi volumi che contenono gli atti del Convegno.

L’esito finale di una iniziativa messa in opera più di una decina di anni fà, quando allora c’era il signor Rollandin, Presidente della Regione, René Faval, Assessore alla Cultura, il Dr. Domenico Prola e Flaminia Montanari alla Soprintendenza delle Belle Arti, si é concrettizzata oggi con questi volumi che contenono gli atti del Convegno.